News

Africa: economic transformation hinges on unlocking potential of cities, says the African Economic Outlook 2016

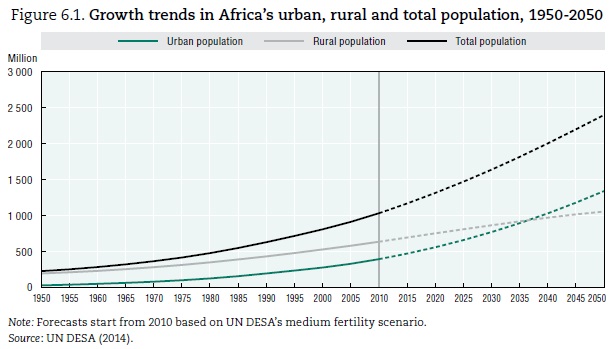

With two-thirds of Africans expected to live in cities by 2050, how Africa urbanises will be critical to the continent’s future growth and development, according to the African Economic Outlook 2016 released today at the African Development Bank Group’s 51st Annual Meetings.

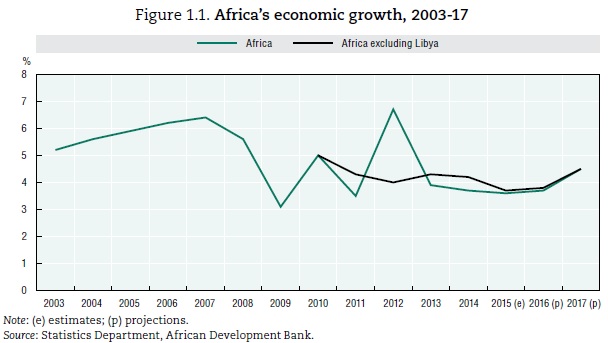

Africa’s economic performance held firm in 2015 amid global headwinds and regional shocks. The continent remained the second fastest growing economic region after East Asia. According to the report’s prudent forecast, the continent’s average growth is expected at 3.7% in 2016 and pick up to 4.5% in 2017, provided the world economy strengthens and commodity prices gradually recover.

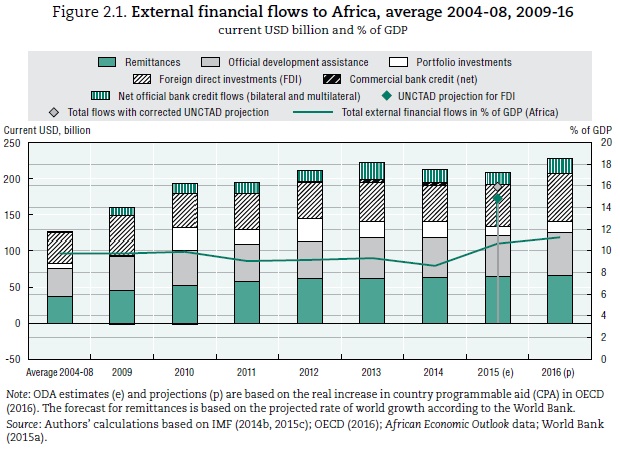

In 2015, net financial flows to Africa were estimated at USD 208 billion, 1.8% lower than in 2014 due to a contraction in investment. At USD 56 billion in 2015, however, official development assistance increased by 4%; and remittances remain the most stable and important single source of external finance at USD 64 billion in 2015.

“African countries, which include top worldwide growth champions, have shown remarkable resilience in the face of global economic adversity. Turning Africa’s steady resilience into better lives for Africans requires strong policy action to promote faster and more inclusive growth,” stated Abebe Shimeles, Acting Director, Development Research Department, at the African Development Bank.

The continent is urbanising at a historically rapid pace coupled with an unprecedented demographic boom: the population living in cities has doubled from 1995 to 472 million in 2015. This phenomenon is unlike what other regions, such as Asia, experienced and is currently accompanied by slow structural transformation, says the report’s special thematic chapter.

According to the authors, lack of urban planning leads to costly urban sprawl. In Accra, Ghana, for example, the population nearly doubled between 1991 and 2000, increasing from 1.3 million to 2.5 million inhabitants – a rise of 92% – at an average annual growth rate of 7.2%. Consequently, the ratio of population to total built up area decreased from 132 inhabitants/ha to 90 inhabitants/ha at an average annual rate of 4.6%, much higher than the global average of 2.1% during the same period.

Urbanisation is a megatrend transforming African societies profoundly. Two-thirds of the investments in urban infrastructure until 2050 have yet to be made. The scope is large for new, wide-ranging urban policies to turn African cities and towns into engines of growth and sustainable development for the continent as a whole.

If harnessed by adequate policies, urbanisation can help advance economic development through higher agricultural productivity, industrialisation, services stimulated by the growth of the middle class, and foreign direct investment in urban corridors. It also can promote social development through safer and inclusive urban housing and robust social safety nets. Finally, it can further sound environmental management by addressing the effects of climate change as well as the scarcity of water and other natural resources, controlling air pollution, developing clean cost-efficient public transportation systems, improving waste collection, and increasing access to energy.

“Africa’s ongoing, multi-faceted urban transition and the densification it produces offer new opportunities for improving economic and social development while protecting the environment in a holistic manner. These openings can be better harnessed to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals – especially SDG 11 on sustainable cities and communities – and the objectives of the African Union’s Agenda 2063,” said Mario Pezzini, Director of the OECD Development Centre and Acting

Director of the OECD Development Co-operation Directorate. “The benefits could accrue for both urban and rural dwellers, provided governments adopt an integrated approach,” he added.

This approach includes stepping up investment in urban infrastructure, improving connectivity with rural areas, better matching formal real estate markets with the housing demand by clarifying land rights, managing the growth of intermediary cities, and improving the provision of infrastructure and services within and between cities. Such investments need to be accompanied by productive formal employment – especially for the youth – and sufficient public goods.

In 2015, approximately 879 million Africans lived in countries with low human development, while 295 million lived in medium and high human development countries. Africa’s youth are particularly at risk from slow human progress. In sub-Saharan Africa nine out of ten working youth are poor or near poor.

According to the Outlook, seizing this urbanisation dividend requires bold policy reforms and planning efforts. For example, tailoring national urban strategies to specific contexts and diverse urban realities and patterns is essential. And harnessing innovative financing instruments is paramount. Ongoing endeavours to promote efficient multi-level governance systems, including decentralisation, capacity building and increased transparency, at all government levels, should be strengthened.

“In 2016, the emerging common African position on urban development and the international New Urban Agenda to be discussed in Quito in October provide the opportunity to begin molding ambitious urbanisation policies into concrete strategies for Africa’s structural transformation,” said Abdoulaye Mar Dieye, the Director of the Regional Bureau for Africa at the United Nations Development Programme. “We need to invest in building economic opportunities, especially those of women of which 92% work in the informal sector. Cities and towns have a key role to play in that process, but only if governments take bold policy action.”

The African Economic Outlook is produced annually by the African Development Bank (AfDB), the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Development Centre and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP).

» Download: African Economic Outlook 2016 (PDF, 6.69 MB)

Executive Summary

The African Economic Outlook 2016 shows that the continent is performing well in regard to economic, social and governance issues and has encouraging prospects for the near future. With its special theme on sustainable cities and structural transformation, this edition looks closely at Africa’s distinctive pathways towards urbanisation and at how this is increasingly shifting economic resources towards more productive activities.

Africa’s economic growth remained resilient in 2015 amid a weak global economy, lower commodity prices and adverse weather conditions in some parts of the continent. Real GDP grew by an average of 3.6% in 2015, higher than the global average growth of 3.1% and more than double that of the euro area. At this growth rate, Africa remained the second fastest growing economy in the world (after emerging Asia), and several African countries were among the world’s fastest growing countries. We forecast that Africa’s economic growth will gradually pick up during 2016/17, predicated on a recovery in the world economy and a gradual rise in commodity prices. However, given the vulnerable global economy and the high volatility of commodity prices, this forecast is uncertain.

Domestic factors have underpinned Africa’s resilience, allowing countries to better cope with the global headwinds. On the supply side, in countries where weather conditions were favourable, agriculture boosted growth, but droughts or floods slowed down growth in countries in East and Southern Africa. In resource-rich countries, growth slowed down as lower commodity prices strained government budgets and affected investment. Manufacturing activity improved in a few countries but was limited by persistent power shortages. On the demand side, private consumption and construction investment remained the main drivers of growth, reflecting relative insulation from external shocks. However, weak global demand curtailed growth of Africa’s exports, especially minerals and oil, and terrorist attacks and general security problems in some countries adversely affected tourism.

Given the increased budgetary pressures in most African countries, keeping debt at sustainable levels has become increasingly important. Governments generally continued to adhere to prudent fiscal policies, limiting spending and improving tax collection. The rapid depreciation in exchange rates and weakening current accounts fuelled a rise in imported inflation. This prompted affected countries to tighten monetary policy to cool down inflationary pressures. Some countries benefited from declining inflation due to lower energy prices. This created additional room for monetary easing through a reduction in interest rates to spur growth.

In 2015, net financial flows to Africa were estimated at USD 208 billion, 1.8% lower than in 2014. Official development assistance rose, but stability in remittances continued to be the main contributing source of Africa’s net financial flows. Sovereign bond issuances rose despite higher interest rates, reflecting general resource starvation among issuing countries. However, direct foreign investment in the oil and metals sectors dropped, as the extractive sector was buffeted by falling commodity prices. Net portfolio equity and commercial bank credit flows dried up, reflecting tight global liquidity conditions and faltering market sentiment. In the wake of slowing growth in large emerging economies, bilateral trade credit suffered as well. Public policies should now aim to stabilise current financing sources and explore new ones, to support infrastructure, training and employment.

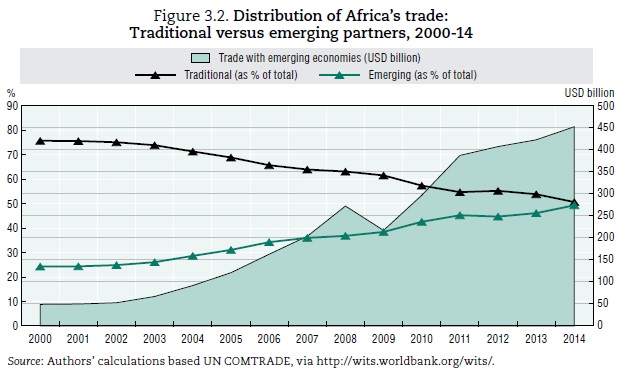

Africa’s growth performance over the past 15 years has created new opportunities for trade. The European Union is likely to continue to be Africa’s main trading partner; however the Tripartite Free Trade Agreement proposed between three of Africa’s largest trade blocs could increase market size, translating into economic benefits. The agreement could narrow income gaps in African countries and help regions integrate financially, provided that governments strengthen structural and regulatory reforms and foster macroeconomic stability. Governments will also need to give pan-African banks a larger role in financing trade, boost capital market liquidity and attract new financial sources to finance intra-regional trade.

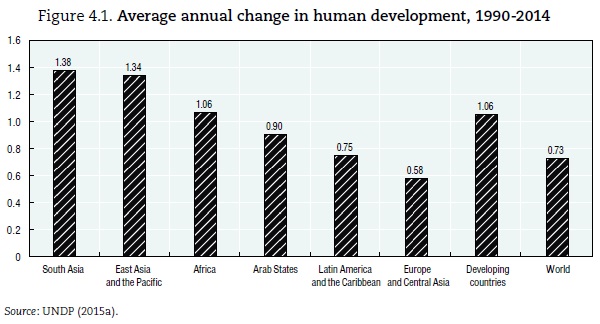

African countries have steadily progressed in enlarging people’s choices in education and health and in improving living standards, but the pace is insufficient. Progress is hampered by inequality between countries, within countries, and between women and men. It is held back by lack of opportunities for the youth, weak structural transformation, especially in sectors dominated by the marginalised groups (including agriculture and informal sectors), and weak investments in gender equality and women empowerment programmes beyond the political sphere. Human progress for rapidly expanding and increasingly mobile populations remains a considerable challenge as espoused in Agendas 2030 and 2063.

Africa’s urbanisation contributes to human development gains but not for everyone. Thus, addressing growing urban poverty should be an integral part of new urbanisation strategies. Underlying tensions between social groups as a result of economic, political and social exclusion can be overcome by ensuring that citizens have secure livelihoods and access to quality services. It also depends on governments enhancing security, promoting human rights and protecting the most vulnerable in society. This will become paramount as African citizens strengthen their demands for better economic opportunities and for more accountable and credible institutions. These demands require an adequate response through sound regulatory policies and effective delivery of public services. Several countries have set good examples that are laying the foundation for reaching developmental goals, including a successful political transition in Burkina Faso in 2015, a Nobel Peace Prize for the Tunisian national dialogue quartet, and successful reforms to health systems in a few other countries.

Africa’s rapid urbanisation represents an immense opportunity, not just for Africa’s urban dwellers but also for rural development. As two-thirds of the investments in urban infrastructure to 2050 have yet to be made, the scope is large for new, wide-ranging urban policies to turn African cities and towns into engines of sustainable structural transformation. The creation of more productive jobs for the rapidly growing urban population is central to achieving this objective. Those new urban policies, at national and local levels, have a key role to play in i) economic development, through higher agricultural productivity, industrialisation and services; ii) social development, targeting safer and inclusive urban housing and robust social safety nets; and iii) sound environmental management, by addressing effects of climate change, scarcity of water and other natural resources, controlling air pollution, developing clean public transportation systems, improved waste collection and increased access to energy. They include stepping up investment in urban infrastructure; improving connectivity with rural areas; matching formal real estate markets better with the housing demand; managing urban land expansion; and developing public mass transport systems within and between cities. The new policies will have to be adapted to the specificities of Africa’s urban realities, tap innovative ways of financing the development of sustainable cities and be implemented through effective multi-level governance systems. In 2016, the common African position on urban development and the emerging international New Urban Agenda offer opportunities to discuss options and start articulating those new urbanisation policies around strategies for Africa’s structural transformation.

In brief

Chapter 1. Africa’s macroeconomic prospects

This chapter looks at macroeconomic conditions in the different regions and countries of Africa, as well as in the continent as a whole. It highlights how weaker oil and commodity prices, uncertain global conditions and domestic political uncertainties are affecting many African economies and explores how their governments are responding to these challenges. It examines Africa’s recent economic growth and prospects for 2016 and 2017 and important driving forces on the demand and the supply side, as well as headwinds from adverse developments in terms of trade, which also affect fiscal positions and current accounts.

Africa achieved impressive economic growth over the past 15 years with the average gross real domestic product (GDP) rising from just above 2% during the 1980-90s to above 5% in 2001-14. In the past two years, growth has been more moderate; this trend is expected to continue in 2016, but strengthen in 2017. Africa’s growth is adversely affected by headwinds from weaknesses in the global economy and price falls of key commodities, but is supported by domestic demand, improved supply conditions, prudent macroeconomic management and favourable external financial flows. The AEO forecast assumes a gradual strengthening of the world economy and the slow recovery of commodity prices. However, given the fragile state of economic recovery and the high volatility of commodity prices this forecast is uncertain.

Growth remained highest in East Africa, followed by West Africa and Central Africa, and is lowest in Southern Africa and North Africa. Assuming gradual improvement in international and domestic conditions, growth is projected to accelerate in all regions in 2016/17. In West Africa, the Ebola epidemic has abated with Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone recovering gradually. Monetary policy stances diverged as countries faced different inflationary and currency pressures.

Monetary policy tightened in countries where current accounts and exchange rates came under pressure and imported inflation increased, however some countries reduced interest rates as inflation declined due to lower energy and food prices. As fiscal pressures intensified governments generally followed prudent fiscal policies. Measures were taken to limit spending and broaden the revenue base.

Chapter 2. External financial flows and tax revenues for Africa

Despite falling commodity prices, Africa’s external financial flows have remained stable overall. This chapter analyses trends in those flows; from foreign direct investment and portfolio equity which fell, to remittances and official development assistance which are increasing. It also studies Africa’s tax revenue collection that has dropped because of lower resource revenues. The chapter looks at the policy challenges and opportunities related to attracting financial inflows ranging from the need to stabilise foreign inflows and implementing medium- to long-term structural policies as part of the African Union’s Agenda 2063 to step up the continent’s development.

The estimated 208.3 billion USD of external finance – foreign investment, trade, aid, remittances and other sources that Africa attracted in 2015 – was 1.8% lower than the previous year. The total sum is projected to rise again to USD 226.5 billion in 2016. Falling commodity prices, particularly for oil and metals, were one of the key causes for the 2015 fall. Portfolio equity and commercial bank credit flows dried up, reflecting tightening global liquidity and a market sentiment wary of risks. Rising remittances and increased official development assistance largely kept the figure up. African governments have to stabilise financial inflows in the short term and use them for sustained economic diversification for the longer term. Falling resource revenues mean governments must also find ways to broaden the tax base away from oil and commodities.

Chapter 3. Trade policies and regional integration in Africa

Accelerated growth in Africa since 2000 has increased the opportunities for enhanced trade while the continent is also looking to step up integration between its regions to further boost growth and job creation. This chapter looks at developments in trade, investment flows, integration and income convergence between regions and countries. It suggests ways for policy makers to spur growth and seize trade opportunities so that the income gap can narrow more speedily. The financial sector, infrastructure and new, bigger free trade areas are all analysed to see how they can help the effort.

Africa must embrace structural and regulatory reforms and enhance financial integration to accelerate efforts that have led to increased exchanges with emerging countries in the rest of the world and between its own countries and regions. Intra-African trade remains below levels seen in other parts of the world but there are ways to change this. While the European Union should remain Africa’s main trade partner for the foreseeable future, an accord between three regional blocs, the Tripartite Free Trade Area, could change Africa’s commercial landscape by increasing market size and creating economies of scale. The gains could also help narrow income gaps between African countries and enhance regional financial integration. African countries must foster macroeconomic stability and improve the investment environment to strengthen the role of pan-African banks in facilitating trade finance and boosting capital markets. Success in stimulating trade and growth depends on the policy and investment climate, depth of financial integration and commitment to reform.

Policy makers need to quickly address three key issues to bolster income convergence in Africa’s regional communities. First, there are huge differences within and between Africa’s regions. Intra-African trade remains the lowest among all the continents. In 2014, trade between regions accounted for approximately 16% of Africa’s total. For Asia, Europe and the Americas, intra-regional trade represented, on average, about 61%, 69% and 56%, respectively, of their total trade in 2014. There are also differences between Africa’s regions. CEMAC has the lowest proportion of intra-regional trade, a commonly used measure of regional integration, at just 2.1% in 2014. This is mainly because of the limited trade integration in this economic zone. The EAC and SADC are Africa’s most integrated regional communities. In 2014, the SADC had the highest proportion of intra-regional trade at 19.3% of its total trade followed by the EAC at 18.4%. WAEMU and SACU had intra-regional trade proportions of 15.3% and 15.7%, respectively.

Chapter 4. Human development in Africa

This chapter reviews Africa’s progress from a human development perspective and provides projections building on current trends. A sub-regional approach is employed to examine the expansion of people’s capabilities in relation to living standards, healthy lives and increasing knowledge. The chapter also explores the negative impact of inequality – including gender inequality – on all levels of human development. Human progress in expanding cities and settlements is considered in the context of the global 2030 Agenda and Africa’s Agenda 2063. The chapter concludes with a range of best practices from country experiences in promoting human progress through more equitable and sustainable human settlements.

African countries have made steady progress with gains in education, health and living standards. However, the pace of progress in human development varies by country and sub-region and is insufficient to reach the 2030 Agenda targets for sustainable development. Progress is hampered by several factors: inequality weakens the impact of growth on poverty reduction, weak structural transformation limits work opportunities, and limited advances in gender equality hamper skills and entrepreneurial development. Ensuring human progress for youthful, rapidly expanding and increasingly mobile populations remains a considerable challenge in all African countries. Work is central to ensuring that Africa’s current urbanisation pathways contribute to gains for all. Policy responses to rising exclusion, urban poverty and inequality are essential to achieve the 2030 Agenda and Agenda 2063 goals for inclusive human development in sustainable cities and settlements. These must address existing tensions between social groups, as a result of economic, political and social exclusion, through the provision of secure livelihoods, quality social services, enhanced security, private sector investment, improved human rights and affordable social protection.

Chapter 5. Political and economic governance in Africa

This chapter assesses the governance trends affecting Africa’s economic outlook by examining the most recent metrics on the functioning of African public institutions. It looks at how the quality of public service delivery and the performance of institutions meet citizens’ expectations. It also lays out the improvements citizens are asking for and how governments are responding. Finally, the chapter outlines the prospects for 2016. Key findings are presented first, and details of how these findings were arrived at are provided in subsequent sections.

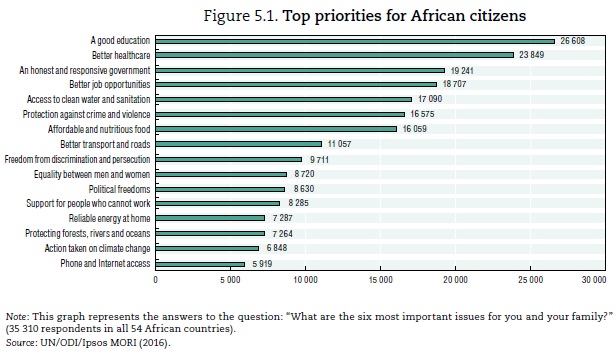

While employment has been the main concern for Africans over the last decade, demands for better services and infrastructure have been on the rise since 2008, and worries about terrorism and violence are less and less confined to conflict zones. Not only are African countries reforming their public institutions, they are also taking their business environments seriously, which can yield economic dividends over the long term but typically has limited impact in the short term. Some indicators and expert reports hint at improvements in rules and regulations affecting businesses.

The severity and geographic scope of politically motivated violence in the form of terrorism or communitarian conflict has been increasing in Africa over the past few years. This has spurred African countries to work together to find regional solutions, but international co‑operation is difficult.

African citizenries are increasingly becoming effective at demanding and obtaining improvements in governance. Success stories include the Nobel-prize winning institutions of Tunisia that managed to create a freer and more democratic society as well as new forms of civil oversight in some countries to give citizens other ways to influence policy beyond voting and protesting.

Theme: Sustainable cities and structural transformation

Africa’s rapid urbanisation represents an immense opportunity, not just for Africa’s urban dwellers but also for rural development. As two-thirds of the investments in urban infrastructure to 2050 have yet to be made, the scope is large for new, wide-ranging urban policies to turn African cities and towns into engines of sustainable structural transformation. Those new urban policies, at national and local levels, have a key role to play in

-

economic development, through higher agricultural productivity, industrialisation and service growth;

-

social development, targeting safer and inclusive urban housing and robust social safety nets; and

-

sound environmental management, by addressing effects of climate change, scarcity of water and other natural resources, controlling air pollution, developing clean public transportation systems, improved waste collection and increased access to energy.

Although policy priorities and sequencing will depend on each country’s specific context, new and ambitious national urban strategies will need to tackle three broad challenges: (i) how to better manage the country’s economic and social spaces in the context of rapid urbanisation; (ii) what governance structures should frame the design and implementation of those strategies; and (iii) how to finance the necessary investment?

Participative, multi-sectoral and place-based national urban strategies can catalyse citizen-led urban development to increase well-being in cities and in their catchment areas. While strategies will necessarily be context-specific, countries will likely have three overarching priorities: accelerating and improving the provision of infrastructure and services; managing the growth of intermediary cities; and clarifying land rights. National and local governments also can draw from a wide range of financial instruments to support urban development. In 2016, the common African position on urban development and the emerging international New Urban Agenda offer opportunities to discuss options and start articulating those new urbanisation policies around strategies for Africa’s structural transformation.

Downloads

- Ch 1. Africa’s macroeconomic prospects | African Economic Outlook 2016 – Part I

- Ch 2. External financial flows and tax revenues for Africa | African Economic Outlook 2016 – Part I

- Ch 3. Trade policies and regional integration in Africa | African Economic Outlook 2016 – Part I

- Ch 4. Human development in Africa | African Economic Outlook 2016 – Part I

- Ch 5. Political and economic governance in Africa | African Economic Outlook 2016 – Part I

- Sustainable cities and structural transformation | African Economic Outlook 2016 – Part II