News

From gloom to boom: governance and economic development in Africa, in sequences

For any serious analysis of development in Africa, we must embrace the fact that there are distinct sovereign countries each with its own economic and development needs and likely policy choices. Perhaps at best we can only generalize about clusters of countries that share broadly similar governance, legal and development circumstances and what policies could apply to each cluster.

Let’s look at some of the data. National populations in sub-Saharan Africa range from that of Nigeria (158.4 million) to that of Seychelles (93,000). In 2014, Africa’s highest estimated GNI per capita that of Equatorial Guinea ($10,210), was 27 times larger than that of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the lowest recorded in the region. In 2013, the estimated GDP per capita of the ten richest African countries was 22.6 times that of the poorest ten. Adult literacy rates in 2013 ranged from 93 percent in Equatorial Guinea to 34 percent in Chad.

In its issue of May 13, 2000, The Economist magazine carried a banner headline calling Africa “The Hopeless Continent” because, it proceeded to argue, of its peoples’ predisposition to bloody civil wars, corruption, civil disorder and tyrannical rulers. It wondered if all these were traceable to an African “inherent character flaw”. In its issue of March 2nd 2013, the same magazine labeled Africa “The hopeful Continent” and proceeded, alongside Time Magazine and The Wall Street Journal to feature the theme of “Africa Rising” as East Asia had done decades earlier. Reforms in national governance, good macro-economic management and new technocratic leadership were the reasons advanced to explain the swift transition from the extreme of hopelessness to the one of a rising Africa.

Uneven development?

As far back as 1958, Albert Hirschman had in The Strategy of Economic Development argued that instead of pursuing the idyll of a “big push” in balanced growth across sectors, and given the conceptual problems of anticipating in advance the setbacks and benefits that would result in such a wide span of major investments, it made more sense to pursue an unbalanced development strategy, where intervention in one sector (like infrastructure) would stimulate cognate productive private investment and vice versa, in a continuing oscillating sequence. Each move would provide market-based incentives for “forward and backward linkages”. This general perspective was repeated in the 2009 World Development Report.

The notion could be applied to sequential transition from economic transformation to law-based governance and vice versa, between sectors, and between countries in an economic integration region. All this is premised on the belief that to declare a national development or governance reform initiative as hopeless – as has happened so often in Africa – it is necessary to overestimate handicaps and underestimate gains.

In Why Economists Got it Wrong, (Zed Books 2015), Morten Jerven argues with ample data, contrary to the argument that the record of Africa’s economic growth has been dismal over the previous six decades, there had been episodes of remarkable economic expansion with rising social indicators in health and education. But growth tends to be cyclical, like everywhere else. Earlier on, Dani Rodrik had detected significant African growth episodes in the years preceding the lost 1980s and 90s decades.

But there was always a number of development and governance scholars of Africa who dissented from the gloom and doom scenario. One of the most remarkable examples is Steven Radelet whose book Emerging Africa: How Seventeen Countries are Leading the Way (Centre for Global Development, 2010), points out the remarkable progress in economic and social indicators in countries from Botswana and Burkina Faso to Uganda and Zambia. Radelet attributes success to more democracy and accountable governance, sensible economic policies, and debt renegotiation, among other reasons. Radelet’s publication came out in the same year as the World Bank’s volume Yes, Africa Can: Success Stories from a Dynamic Continent, edited by Punam Chuhan-Pole and Manka Angwafo, which contained a good number of successful growth experiences combined with governance and institutional reforms that could stimulate contagion in lagging African states through a number of channels.

Still, the situation is mixed. And is mixed even within countries: in Nigeria for instance the state HDI ranges from 0.63 in Akwa Ibom to 0.29 in Yobe. We cannot ignore a number of African countries (and regions in countries) still handicapped by violent political instability, economic regress and famine in the manner portrayed by the iconic “Hopeless Continent” headlines of the 1990s. The challenge is to ensure that the net again in the number of African states with law-based governance in one phase is higher than in the previous one, since some countries in the hopeful category could drop off.

Where do we go from here?

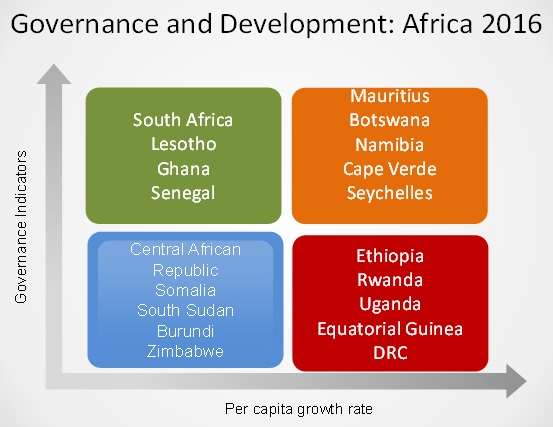

For simplicity, in the upcoming World Development Report 2017, we have categorized a selected number of African countries in a four-cell matrix above with a vertical governance axis and a horizontal economic growth axis. This is a work in progress. But it is a useful indicator of the thought process required in making the intellectual transition from the cross generalizations on Africa, to one characterized not only by diversity but with real possibilities of countries moving to the ideal higher levels of law-based governance with shared prosperity in sequence and through multiple paths. Our goal should be to expand the numbers in the top right quadrant in iterative sequences, coming from several directions.

Michael Chege is Professor at the University of Nairobi.

World Development Report 2017: Governance and the Law

The topic of the 2017 World Development Report will be the role of Governance and the Law in the economic advancement of nations. The flagship report will examine the institutional foundations of a well-functioning state, and address two sets of issues facing the development community: The complicated interaction between economic development and the quality of governance; and the persistence of gaps between intended governance reforms and the reality on the ground. To do this, the Report will demonstrate the importance of taking into account the nature of governance when designing interventions for effective service delivery and human well-being.

The WDR 2017 is being conceived of as part of a trilogy of World Development Reports, alongside WDR 2016 on The Internet for Development and the WDR 2015 on Mind, Society and Behavior, which examine how policy makers can make fuller use of behavioral, technological, and institutional instruments to promote economic development and end poverty.

The report team will engage closely with the World Bank’s new Governance Global Practice and other Global Practices/Cross-Cutting Solutions Areas to advance the analytical framework for governance and institutional reform and draw out operational implications to enhance the capacity of the state to deliver growth, inclusiveness and social progress. To that end, WDR 2017 will convene a high level Advisory Panel on Governance and the Law to advise the Chief Economist and the Governance Global Practice as the World Bank strengthens its overall engagement on governance issues.

Why Governance and the Law?

The effectiveness of measures to end chronic poverty and promote shared prosperity depends crucially on basic governance capacity at all levels of administration. Interventions promoted by development practitioners often implicitly assume that basic governance structures are in place. That is however not the case; our understanding of the policy choices and governance design that can help a developing country achieve inclusive growth remains inadequate. In the absence of hard evidence, governance reforms often mechanically adopt organizational forms from prosperous nations without always generating visible improvement in results or behavior. What the laws and regulations say about the ease of doing business, meritocratic management of civil service, entitlement to social services, and accountability of public finance is frequently in sharp contrast with the actual experience of firms, bureaucrats and citizens.

When do aspirational laws that confirm the principles of participation, rule of law, bureaucratic accountability, and regulatory independence generate momentum for social change? Do persistent implementation gaps harm the legitimacy and trustworthiness of the state? How can we harness the best evidence from around the world to craft more effective systems of governance and delivery mechanisms? The WDR 2017 will attempt to answer these questions.

What Forms of Governance?

The 2017 WDR will outline what governance means for the purpose of the analysis and how its different dimensions can be analyzed in terms of their foundations and implications. The proposed focus is on three elements:

-

The existence of a capable bureaucracy for the effective provision of goods and services;

-

The existence of the rule of law – the presence of norms and legal principles that reflect the beliefs and aspirations of the society, as well as the mechanisms to ensure the impersonal application of norms, and

-

The existence of mechanisms to make governments accountable – to reduce corruption and make the political system more responsive to all groups in society.

These three dimensions of governance will feature prominently in the Report.

The existence of a capable bureaucracy is, on the one hand, related to what determines “quality of government”, in terms of the capacity to effectively deliver services to its citizens – from education and health to citizen security, and the role of subnational and central governments. The “rule of law” dimension, on the other hand, is essential to understanding the nature of the social contract and the interaction between norms and societal beliefs and aspirations.

Finally, a key characteristic of “open access societies” is the existence of accountable government. This dimension requires mechanisms that make the political system competitive and responsive to different groups in society through the existence of accountability and transparency mechanisms. The role of incentives in institutional design and the sustainability and effectiveness of checks and balance systems in organizational design will be discussed, since they are crucial to understanding the interaction between the quality of democracy and the capacity for service provision.

Which are the channels through which a society’s beliefs are eventually transformed into (formal and informal) norms? How do norms interact with the formal legal system? Answering these questions will help us understand why laws that are good on paper are often poorly implemented.

Governance for What?

In addition to its normative importance, Governance and the Law have an instrumental value and must be understood in their relationship to specific outcomes. The Report will consider three main outcome dimensions, corresponding to the questions:

-

What is the interaction between governance and law on the one hand and efficiency, innovation and growth on the other?

-

How do governance and law alter the equality of opportunity, income and wealth; and

-

What is the association of these dimensions with the prevalence, persistence, and attenuation of social conflict?

The WDR will investigate the interactions between the different dimensions of governance and these outcomes.

The WDR 2017 will be co-directed by Luis F. Lopez-Calva and Yongmei Zhou. Luis-Felipe is the Lead Economist in the Poverty Global Practice. From 2007 to 2010, he was the United Nations Development Programme’s Chief Economist for Latin America and the Caribbean. Luis-Felipe has a Ph.D. in Economics from Cornell University. Yongmei Zhou is Governance Advisor in the Governance Global Practice. Yongmei’s work in the Bank has focused on corruption and governance reform; her last assignment was Manager for the Global Center on Conflict, Security and Development. Yongmei has a Ph.D. in Economics from the University of California at Berkeley.