News

Independent power projects in Sub-Saharan Africa: lessons from five key countries

The track record of Sub-Saharan Africa’s power sector is dismal. Two out of three households in Sub-Saharan Africa, close to 600 million people, have no electricity connection. Most countries in the region have pitifully low access rates, including rural areas that are the world’s most underserved. In some countries, less than 5 percent of the rural population has access to electricity.

Chronic power shortages are a primary reason. The region simply does not generate enough electricity. The Republic of Korea alone generates as much electricity as all of Sub-Saharan Africa. Across the region, per capita installed generation capacity is barely one-tenth that of Latin America.

The need for large investments in power generation capacity is obvious, especially in the face of robust economic growth on the continent, which has been the key driver of electricity demand over the last decade. The International Energy Agency predicts that the demand for electricity in Sub-Saharan Africa will increase at a compound average annual growth rate of 4.6 percent, and by 2030 it will be more than double the current electricity production. The World Bank estimated in 2011 that Sub-Saharan Africa needed to add approximately 8 gigawatts (GW) of new generation capacity each year through 2015 (Eberhard and others 2011). But, in fact, over the last decade an average of only 1-2 GW has been added annually.

The cost of addressing the needs of Sub-Saharan Africa’s power sector has been estimated at US$40.8 billion a year, which is equivalent to 6.35 percent of Africa’s gross domestic product (GDP). The existing funding is far below what is needed. This large funding gap cannot be bridged by the public sector alone. Private participation is critical. Historically, most private sector financing has been channeled through independent power projects (IPPs). IPPs are defined as power projects that mainly are privately developed, constructed, operated, and owned; have a significant proportion of private finance; and have long-term power purchase agreements (PPAs) with a utility or another off-taker.

Like any other private investment, IPPs will not materialize in the absence of a suitable enabling environment. The primary objective of this study is to evaluate the experience of IPPs and see what is necessary to maximize their contribution to mitigating Sub-Saharan Africa’s electric power woes.

Investment in Power Generation in Sub-Saharan Africa: An Overview

Current Power Generation Systems in Sub-Saharan Africa

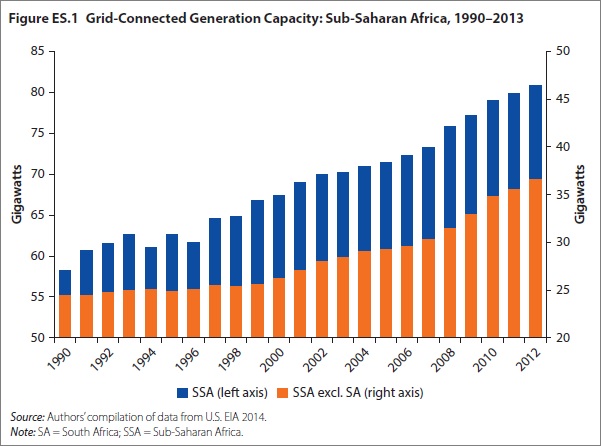

In 2012, the 48 countries of Sub-Saharan Africa had a total grid-connected power generation capacity of only 83 GW. South Africa accounts for over half of this total. The remaining Sub-Saharan African countries have a combined capacity of only 36 GW, and just 13 of these countries have power systems larger than 1 GW. Twenty-seven countries have grid-connected power systems smaller than 500 megawatts (MW), and 14 have systems smaller than 100 MW.

Across Sub-Saharan Africa (excluding South Africa, which uses mostly coal), hydropower contributes just over half the capacity. Fossil fuels, primarily natural gas and diesel or heavy fuel oil, along with some coal, make up almost all the remainder. Renewables such as biomass, geothermal, wind, and solar add about 1 percentage point.

Power Generation Capacity Additions and Investment over the Past 20 Years

Between 1990 and 2013, only 24.85 GW of new generation capacity was added across Sub-Saharan Africa, of which South Africa accounted for 9.2 GW (figure ES.1). In the first decade of this period, 1990 to 2000, the countries of Sub-Saharan Africa other than South Africa added only 1.84 GW, and some even lost capacity. Between 2000 and 2013, investments picked up in these countries with an additional 13.8 GW installed. However, 94 percent of this increase occurred in only 15 countries, leaving dozens that added hardly any capacity at all. And as in the decade between 1990 and 2000, some actually lost capacity. Civil strife and lack of adequate system maintenance were the prevalent causes.

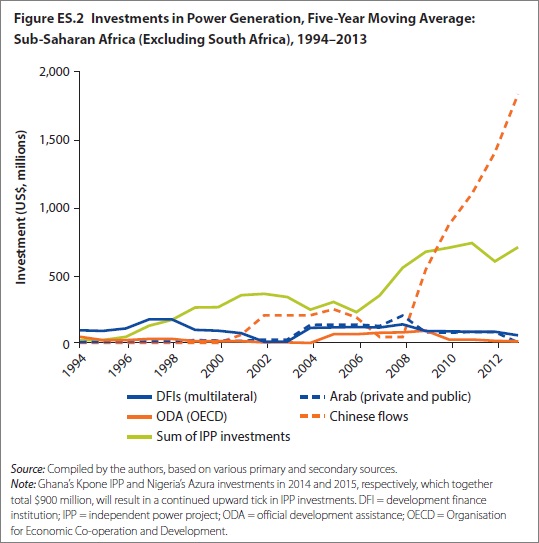

Between 1990 and 2013, investments in new power generation capacity totaled approximately $45.6 billion ($31.3 billion, excluding South Africa), or far below what is required to meet Africa’s growth and development aspirations. Although public utilities have historically been the major sources of funding for new power generation capacity, that trend is changing. Most African governments are unable to fund their power needs, and most utilities do not have investment-grade ratings and so cannot raise sufficient debt at affordable rates. Official development assistance (ODA) and development finance institutions (DFIs) have only partially filled the funding gap. ODA and concessional funding has fluctuated considerably over the past two decades and has recently been overshadowed by IPP and Chinese-supported investment. Indeed, private investments in IPPs and Chinese funding are now the fastest-growing sources of finance for Africa’s power sector (figure ES.2).

Independent Power Projects

IPPs in Sub-Saharan Africa date to 1994. Representing a minority of total generation capacity, IPPs have mainly complemented incumbent state-owned utilities. Nevertheless, IPPs are an important source of new investment in the power sector in a number of African countries.

IPPs are now present in 18 Sub-Saharan countries – all with varying degrees of sector reform and private participation. Currently, 59 projects (greater than 5 MW) are in countries other than South Africa, totaling $11.1 million in investments and 6.8 GW of installed generation capacity. Including South Africa adds 67 more IPPs, bringing the total to 126, with an overall installed capacity of 11 GW and investments of $25.6 billion.

IPPs in Sub-Saharan Africa range in size from a few megawatts to around 600 MW. The overwhelming majority of IPP capacity (82 percent) is thermal; only 18 percent is fueled by renewables. However, there is important growth in renewables. For example, three wind projects reached financial close between 2010 and 2014, and seven small hydropower projects are on the horizon. South Africa procured 3.9 GW in private power between 2012 and 2014, all of which is renewable.

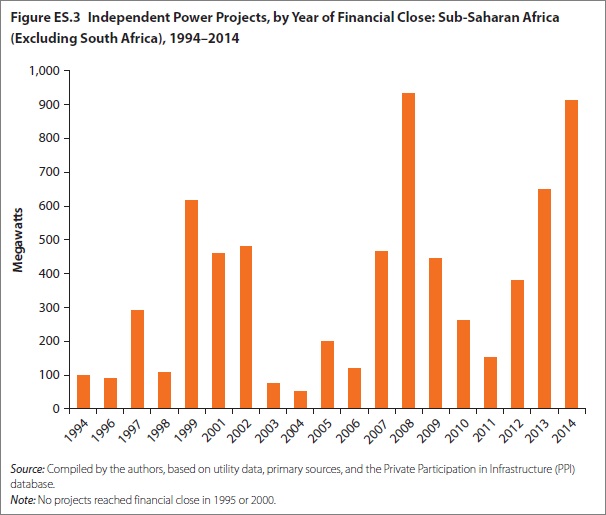

As shown in figure ES.3, there have been three major IPP investment spikes: 1999-2002, 2008, and 2011-2014. The first two spikes were due to the financial close of a small number of comparatively large projects. In 2011, IPP investments began taking off. Excluding South Africa, total IPP investment for projects in Sub-Saharan Africa between 1990 and 2013 was $8.7 billion, whereas in 2014 alone another $2.3 billion was added. Previously, IPP investments in South Africa had lagged those in other Sub-Saharan countries, but between 2012 and 2014 that country closed $14 billion in renewable energy IPPs.

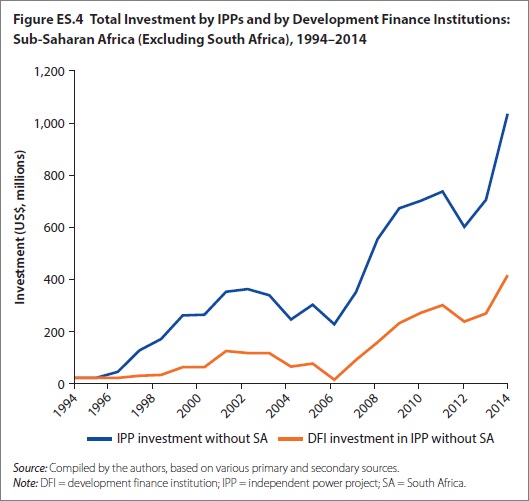

Although the conditions were varied in the countries where IPPs and other private participation took root, certain themes were common. With the exception of South Africa and Mauritius, none of the Sub-Saharan African countries with IPPs had an investment-grade rating. The possibility of a traditional project-financed IPP deal in this climate was limited. DFIs that invest in the private sector have made a significant contribution to funding IPPs (figure ES.4).

Chinese-Funded Power Generation Projects

In addition to IPPs, significant increases in generation capacity have stemmed from Chinese-funded projects. Chinese-funded generation projects can be found in 19 countries in Sub-Saharan Africa. Eight of these countries have IPPs as well as Chinese-funded projects.

Between 1990 and 2014, there were 34 such projects in Sub-Saharan Africa, totaling 7.5 GW. Chinese-funded projects far exceed IPPs in terms of total megawatts, especially for the years 2010-14, with an average size of 226 MW, in contrast to the IPP average of 98 MW. As of 2014, Chinese-funded projects exceeded IPPs in total megawatts and in total dollars invested.

The majority of Chinese-funded projects are large hydropower projects, for which Chinese engineering, procurement, and construction contractors have become renowned worldwide. The typical project structure involves a contractor plus a financing contract. The majority of these projects received funding from the China ExIm Bank (responsible for soft loans and export credit) on behalf of the Chinese government. Additional finance has been provided by other banks owned in whole or part by the Chinese government.

Conclusions

Independent power projects make a significant contribution to meeting Africa’s power needs. There is no doubt that IPPs are worth the effort. But it is not only the quantum of private investment in IPPs that is relevant; equally important are investment outcomes and, especially, the price and reliability of the electricity produced. The challenge ahead is for African countries to create the conditions to attract more and better IPPs and thus help overcome the continent’s power deficit.

Competition still poses a conundrum in Africa, which is why this study pays particular attention to unpacking the trade-offs attached to competitive procurement. When procured competitively, IPPs have generally delivered power at lower costs than directly negotiated projects, and their contracts have held up better. Despite this, unsolicited and directly negotiated deals have been the norm across Sub-Saharan Africa, accounting for over 70 percent of all IPP megawatts procured.

After 20 years of reform efforts in Africa, nowhere on the continent is full wholesale or retail competition to be found in power sectors. Countries that have attracted the most finance have a wide range of sector policies, structures, and regulatory arrangements. In 13 such destinations for IPP investments, vertically integrated, state-owned utilities predominate. The presence of a regulator is also not definitive in attracting investment. Although the countries with the most IPPs all have formally independent regulators, some countries with regulatory agencies do not have any IPPs.

There seems to be no clear relation among reforms, degree of competition, and the success of countries to attract IPPs. Thus it is reasonable to ask what are the merits of competition in this context, and what are the key reform elements that can help African countries most advantageously attract IPPs? Responses to these questions may be condensed into five main conclusions:

-

Systematic and dynamic power sector planning is crucial to identifying the generation projects that best meet a country’s power needs and define the potential space for IPPs. Sound planning means that countries are able to project future electricity demand correctly, decide on best supply (or demand management) options, and anticipate how long it would take to procure, finance, and build the required generation capacity. Planning tools must be updated regularly and new building opportunities allocated based on clear criteria. Finally, there must be an explicit link between planning and the timely initiation of the generation procurement process.

-

Competitive procurement of IPPs helps ensure that projects are implemented transparently and at the lowest cost. Two decades of experience in power procurement in Sub-Saharan Africa have amply demonstrated that a lack of competition in procuring new generation capacity has extensive drawbacks, ranging from immediate effects on project outcomes (higher prices, unraveling contracts, and so on) to more general effects on the overall governance of the electricity sector and its investment climate. IPP investment in Africa will rely on long-term contracts with off-takers where electricity demand is growing at medium or high rates. Where long-term contracts for new power are competitively bid rather than directly negotiated, there is a potential for reduced prices. Also, competitive procurement can stimulate the development of potentially bankable projects, especially renewable energy. African governments have not done enough to offer competitive tenders or auctions with clear ground rules; standardized, long-term contracts with IPPs; and reliable timelines. In the absence of these, project developers and funders have offered unsolicited bids. Designing and running competitive tenders are not trivial tasks. But if a core government team is authorized to do the work and sufficient resources are allocated for this purpose, then experienced transaction advisers can be hired to help. And the benefits of lower prices invariably justify the initial cost of running these tenders.

-

Direct negotiations and unsolicited offers are not ruled out. Indeed, sometimes they are unavoidable, but governments that engage in unsolicited proposals or directly negotiated deals must develop the capacity to properly assess the costcompetitiveness of these projects and the technical and financial capabilities of the project developers – thereby negotiating cost-competitive contracts. In addition, unsolicited bids may be opened to more scrutiny by instituting a public tender.

-

The financial viability of utilities is a critical factor in attracting IPP investments. IPP contracts should be undertaken with financially viable off-takers, whether they be utilities or large customers. Most IPPs are project-financed, and their bankability rests on secure revenue flows. Although credit enhancement and security measures can mitigate risk, a financially strong off-taker provides a sustainable basis for securing long-term contracts with IPPs. A sustained effort to better the performance of utilities must be at the center of countries’ reform agendas and also be consistently supported by development partners through financial and technical assistance.

-

Reforms, especially those improving the investment climate, remain important. Although IPP investment trends do not appear to be correlated with specific power sector institutional arrangements, the importance of reforms geared toward promoting a sound investment climate should not be discounted. Unraveling potential conflicts of interest between incumbent state-owned generators and IPPs, through unbundling generation from transmission, is in principle positive for private investment, as is more transparent contracting among state generators, IPPs, and independent transmission companies and system operators. Having a regulator in place is especially important, but the mere existence of a regulatory agency is not enough. The quality of regulation capacity is non-negotiable: the regulator must be independent and endowed with competent – and sufficient – human resources.

In conclusion, investment in Africa’s power sector IPPs is growing, but not fast enough. The region does not have sufficient power. All sources of investment need to be encouraged. For IPPs to flourish, the countries of Sub-Saharan Africa need dynamic, least-cost planning, linked to the timely initiation of the competitive procurement of new generation capacity. This must be accompanied by building an effective regulatory capacity that encourages the distribution utilities that purchase power to improve their performance and prospects for financial sustainability – and to widen access to electricity. Such efforts promise to promote economic and social development across the region.

Five Case Studies

1. Kenya’s Electric Power Promise

Kenya is among the countries in Sub-Saharan Africa with the most extensive experience in independent power projects (IPPs). Its first IPPs date back to 1996, and since then the country has closed a total of 11 projects for a total of approximately 1,065 megawatts (MW) and $2.4 billion in investment. While from a global standpoint these numbers are small, IPPs will soon represent more than one-third of Kenya’s total installed generation capacity. Most of the plants procured over the past two decades use medium-speed diesel/heavy fuel oil (MSD/HFO); some are geothermal and wind plants. And more IPPs are on the way: for example, in September 2014, a 900-1,000 MW coal plant was awarded to a consortium led by the Kenyan companies Gulf Energy and Centum Investment Company. Despite this momentum, the actual process of procuring new geothermal and wind power has become more muddled and complex with a series of procurements conducted by the publicly owned Geothermal Development Company (GDC) and directly negotiated wind projects.

What can be learned from Kenya’s IPP experience, particularly in terms of planning, procurement, and contracting? How do Kenya’s IPPs measure up to their public counterparts, and what areas might require further improvement?

2. Independent Power Projects and Power Sector Reform in Nigeria

While Nigeria has the largest population and economy on the African continent, 46 percent of its citizens live below the poverty line and less than 50 percent have access to electricity. The demand for electricity far outweighs available capacity, which is less than 5 gigawatts (GW) for a population of about 170 million (Compare this with South Africa, which has an installed capacity of 43 megawatts [MW] for a population one-third the size of Nigeria’s.) The actual generation output rate in Nigeria, meanwhile, is far below installed capacity. In fact Nigeria’s output rate per capita is among the lowest in the world, owing to poor operation and maintenance, aging generation and transmission infrastructure, fuel supply constraints, and vandalism.

Nonetheless, Nigeria has embarked on the most ambitious electricity sector reform effort of any country in Africa. Reforms were initiated in 2001 with the publication of a new power policy. The objectives of the reforms were to improve efficiency, attract private participation, and strengthen power sector performance so as to enable economic and social development. To this end, policy makers set a goal of achieving 40 GW of capacity by 2020 – a goal that now seems out of reach.

As part of the reform process, Nigeria unbundled the generation, transmission, and distribution subsectors; privatized power generation stations and distribution utilities; appointed a private management contractor to manage the transmission company; and established a bulk trader. Barring South Africa, the country also boasts the largest investment in independent power projects (IPPs) in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Since 1998, five large IPPs have been developed. Several generations of IPP transactions may be attached to distinct phases of the sector reform process. The first generation of IPPs emerged before the reforms began in earnest and included a project-financed plant. A second generation of IPPs was developed after President Olusegun Obasanjo took office in 1999 and the new power sector policy was published in subsequent years. Two stopgap projects emerged during this period, financed by international oil companies (IOCs) and with equity contributions from the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation. After a hiatus of a number of years, and the rejuvenation of the reform process under President Goodluck Jonathan, who took office in 2010, a third generation of IPPs was developed including a predominantly Nigerian-financed IPP that intends to serve a local grid with mainly industrial demand. Today, a new power market is being established, and a fourth generation of classic, project-financed IPPs is emerging. IPP contracts have had to be designed and negotiated afresh in the new market conditions, and appropriate credit enhancement and security measures put in place to mitigate payment and termination risks.

Nigeria thus represents a fascinating case study of accelerating investment in new power capacity, in an electricity sector undergoing radical reform. Will the next generation of IPPs be successful and lead to further investment in much-needed power generation capacity? Will risks be mitigated? Will sector reforms foster financial sustainability? Will greater competition be possible in the future?

3. Investment in Power Generation in South Africa

South Africa is a latecomer in introducing private investment and independent power projects (IPPs) into its electricity sector. For nearly a century, its national electricity utility, Eskom, dominated the power market. Various attempts to introduce IPPs were half-hearted and unsuccessful. However, this has changed during the past four years.

South Africa now occupies a central position in the global debate about how best to accelerate and sustain private investment in renewable energy. In 2009, the government began exploring feed-in tariffs (FiTs) for renewable energy, but these were rejected in favor of competitive tenders. The resulting program, known as the Renewable Energy Independent Power Project Procurement Programme (REIPPPP), has successfully channeled substantial private sector expertise and investments into grid-connected renewable energy in South Africa at competitive prices.

To date, 92 projects have been awarded to the private sector, and the first projects are already online. Private sector investments of more than $19 billion have been committed for projects that total 6,327 megawatt (MW) of renewable energy. Prices of renewable energy dropped during the four bidding phases, with average solar photovoltaic (PV) tariffs decreasing by 71 percent and wind dropping by 48 percent in nominal terms. Most impressively, these achievements occurred during a four-year period, from 2011 to 2015. Additionally, there have been notable improvements in economic development that have primarily benefitted rural communities. Important lessons can be learned from this process for both South Africa and other emerging markets contemplating investments in renewable energy and other power sources.

4. Power Generation Results Now, Tanzania!

Tanzania has a vast array of conventional and renewable energy resources, and yet the country struggles to generate sufficient power to fuel growth and development. It has only 1,583 megawatts (MW) in installed generation, and imported fuel is a critical piece of its electric power generation. Network failures undermine what little power is produced. As a result, approximately 46 percent of the nation’s total power consumption is from off-grid self-generation (averaging $0.35/kilowatt-hours, kWh).

What has prevented Tanzania from harnessing its domestic resources in an economically efficient way, and what may be done differently going forward? There appear to be three key elements that directly affect Tanzania’s electricity supply industry and generation procurement. The first is a lack of coherent and up-to-date planning; the second is related to the planning and contracting nexus, including the allocation of public and private generation projects. The third element is a lack of sustained commitment to private sector investment and competitive bidding practices. The gas sector also suffers from many of the same issues, with direct implications for power production.

5. Power Generation Developments in Uganda

Uganda occupies a unique space in the history of power sector reform and investment in Africa. It was the first country to unbundle generation, transmission, and distribution into separate utilities and to offer separate, private concessions for power generation and distribution. Critics said that Uganda’s power system was too small to reap the possible benefits that might flow from competition in generation, and more focused management of transmission and distribution (T&D). The years that immediately followed the reforms seemed to bear out the critics’ views: the private distribution operator struggled to reduce losses, and there were delays in investments in large new hydropower capacity, resulting in costly dependence on short-term thermal power.

Despite ongoing challenges, Uganda’s power sector reforms are now bearing fruit. The performance of the distribution utility has improved. Losses are down, and collections, investment, and connections are up, although access rates remain low. After a torturous start, Uganda concluded the largest private hydropower investment in Africa, the Bujagali plant, built by an independent power project (IPP). Simultaneously, it has attracted a raft of smaller IPP investments, including the innovative competitive bids for small hydropower, biomass, and solar projects solicited under the global energy transfer feed-in tariff (GETFiT) program, which was developed jointly by Uganda’s Electricity Regulatory Authority (ERA) and the Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau (KfW, German Development Bank). After South Africa, Uganda has the largest number of IPPs in Sub-Saharan Africa and the only other competitively bid grid-connected solar photovoltaic (PV) program.

Alongside these IPP successes, Uganda has now embarked on two large Chinese-funded hydropower projects. Private investment in power is still politically contested, and IPPs are seen locally to be potentially expensive, complex, and time-consuming.

Uganda thus offers much pertinent experience and many valuable lessons in power sector reform, private sector participation, IPPs, competitive bidding, grid-connected renewable energy, and Chinese-supported projects.