News

IMF Executive Board 2016 Article IV Consultation with Nigeria

On March, 30, 2016, the Executive Board of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) concluded the Article IV consultation with Nigeria.

The Nigerian economy is facing substantial challenges. While the non-oil sector accounts for 90 percent of GDP, the oil sector plays a central role in the economy. Lower oil prices have significantly affected the fiscal and external accounts, decimating government revenues to just 7.8 percent of GDP and resulting in the doubling of the general government deficit to about 3.7 percent of GDP in 2015. Exports dropped about 40 percent in 2015, pushing the current account from a surplus of 0.2 percent of GDP to a deficit projected at 2.4 percent of GDP. With foreign portfolio inflows slowing significantly, reserves fell to $28.3 billion at end-2015. Exchange restrictions introduced by the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) to protect reserves have impacted significantly segments of the private sector that depend on an adequate supply of foreign currencies.

Coupled with fuel shortages in the first half of the year and lower investor confidence, growth slowed sharply from 6.3 percent in 2014 to an estimated 2.7 percent in 2015, weakening corporate balance sheets, lowering the resilience of the banking system, and likely reversing progress in reducing unemployment and poverty. Inflation increased to 9.6 percent in January (up from 7.9 percent in December, 2014), above the CBN’s medium-term target range of 6-9 percent.

The recovery in economic activity is likely to be modest over the medium term, but with significant downside risks. Growth in 2016 is expected to decline further to 2.3 percent, with non-oil sector growth projected to slow from 3.6 percent in 2015 to 3.1 percent in 2016 before recovering to 3.5 percent in 2017, based on the results of policies under implementation – particularly in the oil sector – as well as an improvement in the terms of trade.

The general government deficit is projected to widen somewhat in 2016 before improving in 2017, while the external current account deficit is likely to worsen further. Key risks to the outlook include lower oil prices, shortfalls in non-oil revenues, a further deterioration in finances of state and local Governments, deepening disruptions in private sector activity due to constraints on access to foreign exchange, and resurgence in security concerns.

Staff Report

The Nigerian economy is facing substantial challenges. Low oil prices, a lengthy period of policy uncertainty, and ongoing security concerns, have produced: a widening fiscal gap with salary arrears at state and local governments; a weaker external current account and the introduction of exchange restrictions as international reserves declined; lower financial sector resilience; and sharply slower growth. These shocks have compounded an already challenging development environment – inadequate infrastructure, high unemployment (9.9 percent) and a high poverty rate (above 50 percent in the northern states).

Growth is expected to slow further in 2016 before a modest recovery over the medium term, but with significant downside risks and reduced buffers. Some components of the policy package to adjust to the permanent terms of trade shock are now in place but with little improvement expected in external conditions and large policy distortions remaining, growth is likely to remain well below historical averages. There are significant risks to this outlook: uncertainty on the path of oil prices and oil production; the impact of reforms to raise non-oil revenues; late disbursement of external financing or less-than-desired access to international markets; a further deterioration in the fiscal position of state and local governments; and disruption to private sector activity due to exchange restrictions. Meeting fiscal slippages through additional domestic borrowing could raise the Federal government interest payment-to-revenue ratio to an unsustainable level and crowd out lending to the private sector. The combination of wide fiscal deficits and accommodative monetary policy with an overvalued exchange rate could widen the current account deficit further, add pressure to the exchange rate and international reserves, and result in further delays in much needed foreign capital inflows and investment.

In light of the significant macroeconomic adjustment needed, it will be important to initiate urgently a coherent package of policies anchored on: (i) safeguarding fiscal sustainability; (ii) reducing external imbalances (including real exchange rate realignment); (iii) enhancing resilience and further improving the efficiency of the banking sector; and (iv) implementing structural reforms for sustained and inclusive growth.

Background: A Challenging Environment

Nigeria’s economy has been hit hard by global developments that have aggravated longstanding development weaknesses. Three major economic transitions – the slowdown and rebalancing of the Chinese economy, lower commodity prices, and tightening financial conditions and risk aversion of international investors – have impacted the Nigerian economy through trade, exchange rates, asset markets (including commodity prices), and capital flows. These shocks compounded an already challenging development environment – inadequate infrastructure, high unemployment (9.9 percent), and a high poverty rate (above 50 percent in the northern states).

Macro-financial outcomes are closely linked with the price of oil. While the non-oil sector accounts for 90 percent of GDP, the oil sector plays a central role in the economy. With the fiscal and external accounts highly dependent on oil receipts, lower oil prices reduce aggregate demand from the public sector and affect growth in the non-oil sector through consumption, investment, asset (including equity) prices, and cost channels. A lower supply of foreign exchange adversely impacts corporate sector activity, and combined with high costs of doing business (inadequate infrastructure, low access to credit, and high interest rates) weakens balance sheets in corporate and banking sectors and lowers investment and growth. Although the banking sector is relatively small (about 20 percent of GDP), the transmission of shocks has widespread impact as conditions in the formal sector have trickle-down effects on informal credit and trading activities.

Policy uncertainty amplified the impact of global developments. President Buhari was inaugurated in May 2015, having led the All Progressives Congress (APC) – a merger of four opposition parties – to victory in the March 28 elections, the first democratic transition of government in Nigeria’s history. The administration has listed fighting corruption, enhancing transparency, improving security, and creating jobs as key elements of its policy agenda. While progress has been made against Boko Haram, in addressing corruption, and strengthening governance, the delay in appointing a cabinet until November 2015 limited the scope for a timely and comprehensive policy response to the oil price shock.

Capacity constraints have also limited the policy response. Following the recommendations of the 2014 Article IV consultation, progress has been made in improving capacity, in particular in public financial management (PFM) at the federal government level, helping to strengthen fiscal discipline and accountability. This effort is now being extended to the State and Local Governments (SLGs).

Policy Discussions: Urgency in Dealing With the Impact of the Oil Price Shock

Changing the Nature of Government

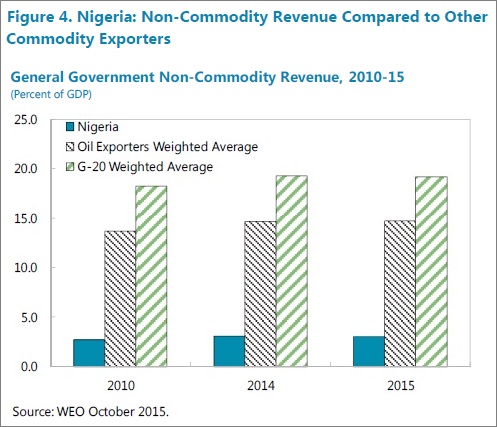

The urgently needed near-term fiscal adjustment should be used to jump start medium-term fiscal policy goals – delivery of key public services. The new reality of low oil prices and low oil revenues means that the nature of government – all tiers of government – needs to fundamentally change. The fiscal challenge is no longer about how to divide the proceeds of Nigeria’s oil wealth, but what needs to be done to effectively deliver public services, be it in education, health, or infrastructure. In this context, immediate fiscal adjustment is unavoidable. With the lowest non-oil revenues among major commodity producers (Figure 4) and consolidated government spending already relatively low (11½ percent of GDP in 2015), the fiscal adjustment should be tilted to raising revenues.

A fiscal adjustment of about 3 percent of GDP is needed to ensure medium-term debt sustainability. While public debt is low at 14.4 percent of GDP, the FGN interest payments-to-revenue ratio has increased significantly to about 32 percent. With the sharp decline in the growth rate and despite the recent reduction in domestic real interest rates, the overall primary balance required to keep debt on a sustainable path is now at about -1 percent of GDP (see Annex III). This implies that the primary balance (currently at about -4 percent of GDP) needs to be adjusted by 3 percent of GDP. The 3-percent fiscal adjustment will also ensure that the long-term management of the oil wealth remains sound and sustainable (SIP on fiscal rules). Efforts toward fiscal consolidation in the draft 2016 budget are in the right direction, but with oil prices expected to remain low (and below oil price in the draft budget) more will be needed.

The composition of the adjustment should reflect a realistic pace for raising non-oil revenue, which is critical to allow budget to be implemented. At just 4 percent of GDP, non-oil revenues are simply too low for the government to be able to meet its expenditure priorities, including addressing lagging indicators for infrastructure and social development (Figure 4). Reforms could target a non-oil revenue-to-non-oil-GDP ratio that is more in line with that of peers and yet achievable, such as 8 percent over the medium term (against a target of 6.4 under the current policies). Such an objective could be achieved, as a priority, by raising the standard VAT rate initially from 5 percent to 7.5 percent and further over the medium term to provide a strong revenue base for SLG s (85 percent is distributed to SLGs), in addition, broadening the base (from currently 16 percent of GDP to about 50 percent of GDP), and revamping the design to allow the offsetting of input tax credits. Another priority is the strengthening of tax administration for corporate income tax and customs taxes and excises, which can increase collection efficiency by 20 percent by closing loopholes, reducing tax exemptions, and improving compliance. In particular, as an immediate revenue protection measure government could announce a moratorium on new tax incentives, which would stem revenue losses until an overall review of the Nigerian income tax system is concluded. While the draft 2016 budget prioritizes early action on administrative improvements – and steps are underway – adjustment in tax rates could provide greater certainty that revenue objectives could be achieved.

Authorities’ views: The authorities acknowledged the importance of non-oil revenue mobilization, especially in the context of permanently lower oil prices. They are open to consider an increase in the VAT rate over the medium term, but believe that a sufficient increase in revenue effort can result immediately from strengthening collection efficiency, with a focus on broadening the base, improving compliance, closing loopholes, and reducing tax exemptions.

Streamlining recurrent expenditure is key to ensure the efficiency of public service delivery and foster fiscal adjustment.

-

The establishment of an Efficiency-Unit is a promising and important initiative to streamline the cost of government and improve efficiency of public service. A mechanism could also be introduced to promote cooperation with SLGs, strengthening expenditure rationalization across tiers of government. The broader streamlining review could also incorporate a strategic prioritization of spending towards high sustained growth and social development.

-

Tax expenditures could be reduced to create space for higher-priority spending. Tax exemptions/incentives should be streamlined and phased. Where they exist, sunset clauses should be well-specified, and there should be a strict cost-benefit assessment, with strong monitoring of outcome-based performance indicators.

-

Transfers should be well targeted. In particular, continuing the move (in the draft 2016 budget) to eliminate resources allocated to fuel subsidies would allow spending on innovative social programs for the most needy and for other public services. With regulated prices only just covering current costs, any increases in international prices (and/or currency depreciation) will require a decision on whether to discontinue the subsidy regime or request a supplementary budget (as occurred in 2015).

Authorities’ views: The authorities indicated that in the Medium Term Expenditure Framework (MTEF) for 2016-18, recurrent expenditure as a share of nominal GDP is projected to be broadly contained, from 2.6 percent of GDP in 2015 to 2.3 percent in 2018 (based on authorities GDP numbers). The authorities see scope for streamlining further, beyond measures reflected in the draft 2016 budget. They noted that they have already taken steps to contain recurrent expenditure at the Federal level through a Zero-Based Budgeting approach. On fuel subsidies, they noted that no provision is needed, given low oil prices. They stressed, however, that they would be clearing arrears to oil marketers, and reviewing product pricing on a quarterly basis.

Implementing Structural Reforms

Nigeria suffers from a serious infrastructure deficit. Without power and transportation, Nigeria’s cost of production remains high and domestic production uncompetitive. Various efforts are ongoing and will require a sustained effort over the long term to bridge the substantial deficit. In that regard, prioritization and cost-benefit analysis of potential infrastructure projects are critical. Reducing the cost of production by ensuring functioning transportation and power supply networks will help offset the impact of the appreciation of the real effective exchange rate that occurred over the past five years. Authorities’ views: Relevant ministries such the Budget and Planning, Power, Works, and Housing, and Transportation have started planning for the development of much needed infrastructure. The authorities acknowledge the constrained environment they have to work under and are focusing on prioritizing near-completed, high-impact projects that are consistent with the government development strategy, and on creating an enabling environment to attract investment. They are also reviewing projects suitable for PPPs, and have completed some feasibility studies. The authorities recognize also the importance of monitoring and evaluation (M&E) of projects and to continue publishing those reports periodically to enhance transparency and regain confidence in the government.

Access to credit remains poor, especially for Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs). It is important to continue providing support for MSMEs, promoting the use of financial services, and improving financial infrastructure. Efforts to increase financial inclusion, however, have become more challenging, given that both the corporate and banking sectors are leveraged and impacted by the oil price shock and the consequent slowdown in economic activity.

Authorities’ views: The authorities acknowledged the challenges faced by MSMEs in accessing credit. They noted that a number of steps are already being implemented to address these challenges, including establishing the Development Bank of Nigeria (DBN) and the Movable Asset Collateral Registry (MACR) at the CBN. The DBN has received funding commitments of over $1.5 billion (N300 billion) from international finance institutions (IFIs) and the Federal Government of Nigeria and is expected to commence operations by mid-2016. The DBN is expected to provide MSMEs with loans of up to 10 years and up to 18 months moratorium. The MACR is to be launched by the CBN in the first quarter of 2016 and will enable individuals to obtain loans from financial institutions using movable assets and intellectual property as collateral.

Given demographics, the pace of job creation needs accelerating. Key initiatives have focused on supporting the agriculture industry, which could reduce migration of youth to the urban areas and lower youth unemployment. Subject to review, it will be important to scale-up recent government pilot programs to improve access to agricultural inputs, the use of conditional cash transfer schemes linked to girls’ enrolment in schools, and delivery of gender-based initiatives (Annex V).

Plans to improve governance, in particular of the oil sector, should be implemented expeditiously. At the Nigeria National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC), the senior management was replaced and financial management improved by migrating accounting processes to the Treasury Single Account (TSA). The passage of the revised Petroleum Industry Bill (PIB) is also expected to strengthen governance in the sector. The government also took initiatives to strengthen policies against corruption and oil theft. Targeted Anti-Money Laundering/Combating the Financing of Terrorism (AML/CFT) measures can play an important role in tackling theft and corruption in the oil sector by tracing the associated financial flows. Efforts to improve the understanding of the pattern of such flows should be pursued, notably by completing the national risk assessment to enhance the effectiveness of banks’ AML/CFT controls and CBN’s supervision. Further, AML/CFT risks of BDCs need to be properly mitigated (see Appendix II).

Authorities’ views: The authorities highlighted the new administration’s commitment to fighting corruption. They view the plan to restructure the NNPC as a promising step forward to enhance transparency and accountability of the oil sector. They concur that effective implementation of targeted AML/CFT measures, including tracing financial flows, could facilitate detection and investigation and help tackle economic crimes such as oil theft and corruption.

Box 3. Nigeria: Non-oil Revenue Mobilization[1]

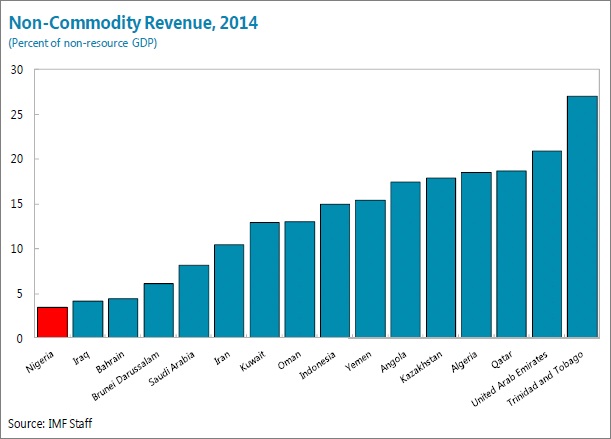

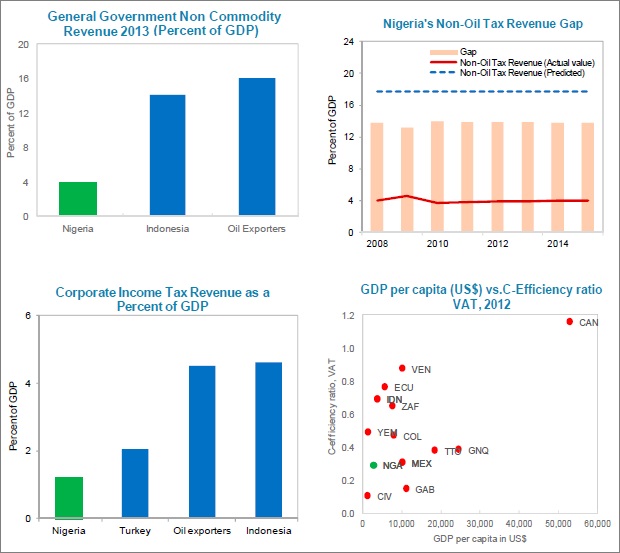

Nigeria’s non-oil revenue is one of the lowest among major commodity producers. In 2014, non-oil tax revenue was estimated at only 4 percent of GDP, far below the average of 15 percent of GDP for other oil exporters. Increasing fiscal space through more non-oil revenue collection holds the keys for a growth and social-friendly orientation of the Nigerian economy.

There is scope to improve Nigeria’s revenue-to-GDP fourfold. Crivelli and Gupta (2014) study the non-resource tax effort in 35 resource-rich countries (including Nigeria) over 1992-2009 and find that each additional percentage point of GDP of resource revenue reduces non-resource revenues by 0.3-0.4 percentage points of GDP. In addition, the share of agriculture in GDP is negatively related to tax revenue, with magnitude similar to the impact of resource revenue, while inflation is positively related. Applying their estimated elasticities to Nigeria’s current economic conditions suggest that non-oil tax potential could be about 18 percent of GDP.

The low tax performance in the non-oil sector reflects a combination of tax rates, exemptions, and enforcement issues on VAT, CIT, and customs and excises. VAT collection efficiency is low compared to other oil exporters, owing to the rate and design. At 5 percent, Nigeria has one of the lowest VAT rates in the World, well below the regional ECOWAS requirement of 10 percent. In addition, the current VAT is not neutral, as it disallows input tax credits to businesses on purchases of capital goods, thereby imposing a consumption tax on real investments and undermining competitiveness. CIT performance is below peers. Despite a rate slightly above comparators, CIT revenue is much lower (1.5 percent of GDP against an average of 5 percent in other oil exporters). The wide use of exemptions and poor compliance are two important factors explaining the relatively low CIT collection.

In the medium term, fiscal reforms should focus on increasing collection efforts on various taxes, including improving compliance across the board. Raising the standard VAT rate and permitting the offsetting of input tax credits could be early actions, while a tax on mobile phone transactions could be introduced gradually. In addition, CIT collection could benefit from the closing of loopholes, reducing tax exemptions, and improving compliance, while excise taxes could be increased on alcohol and tobacco.

[1] Prepared by S. Tapsoba and K. Young.

Selected Issues

Options and strategies for a fiscal rule for Nigeria’s oil wealth management

Despite a diversified economy, Nigeria’s fiscal policy is heavily dependent on the oil sector. With oil price falling, Nigeria’s fiscal authorities are faced with significant challenges. Oil revenues have declined, limiting fiscal spending and fiscal buffers have been almost depleted. Setting Nigeria’s fiscal policy on a more sustainable course is needed going forward. In the presence of sizeable revenue derived from oil, the near-term priority should focus on better and effective management of oil wealth. To that effect, a sound fiscal framework is needed.

In this chapter, options for a formalized rule-based approach to setting a “depoliticized” budget oil price are being explored. This formula is designed to be consistent with long-term fiscal sustainability, while ensuring needed accumulation of fiscal buffers. Options for the appropriate accompanying institutions are also examined. The paper finds that a budget rule using a combination of past 5-year average oil price, the current year oil price, and forward looking 5-year oil-price, together with a structural primary surplus target of 2½ percent of non-oil GDP, is one option (subject to pre-announced exceptions) that could provide a basis for long-term sustainability and the preservation of oil wealth, while limiting the effect of oil price volatility.

Enhancing the effectiveness of monetary policy in Nigeria

Two episodes of a boom and a bust since early 2000 have highlighted the challenges in the current monetary policy framework. In particular, the sharp decline in oil production in 2013, followed by a sharp decline in oil prices in 2014, have severely tested the current framework. This paper reviews the effectiveness of the current framework and makes a number of policy recommendations to enhance the resilience of Nigeria to future shocks of a similar nature.

Capital flows to Nigeria: recent developments and prospects

This paper examines recent developments in capital flows to Nigeria, and prospects for flows in the near term. While data on capital flows is subject to limitations, especially on capturing outflows, Nigeria has enjoyed increased international capital flows from a broad array of sources in recent years, though these have declined since 2014. Key drivers of capital inflows have been Nigerian and external interest rates, oil prices, and risk aversion among international investors. Some of these factors, including recent monetary easing, low oil prices expected for a long period, administrative measures inhibiting activity in the interbank foreign exchange market, and market participants expecting the naira to weaken, are likely to weigh on the outlook for capital flows in the near term.

Financial deepening and the non-oil sector growth in Nigeria

Nigeria’s recent growth has been supported by the strong growth in the non-oil sector. It is important to investigate how much of the non-oil growth was associated with the oil price boom. In particular, it is important to understand how the growth in the oil sector was transmitted to the non-oil sector growth, both by raising aggregate demand in the economy but also by raising aggregate supply and potential output of the non-oil sector. The channel of transmission through the aggregate demand channel was analyzed in the 2014 Article IV using the input-output table. The transmission through the aggregate supply channel, in particular by financing investment (both fixed capital formation and working capital) in the non-oil sector is less understood.

Better understanding of the magnitudes of spillovers through the aggregate supply side of the economy is important at this juncture as the reversal of oil price boom observed since summer 2014 could result in not only a decline in the aggregate demand but also in the aggregate supply and potential output which could have a lasting effect on the long-run growth.