News

Overview of recent economic and social developments in Africa

Report prepared for the Ninth Joint AUC-ECA Annual Meetings of the AU Conference of Ministers of the Economy and Finance and ECA Conference of African Ministers of Finance, Planning and Economic Development, taking place from 31 March to 4 April 2016 under the theme: “Towards an Integrated and Coherent Approach to Implementation, Monitoring and Evaluation of Agenda 2063 and the SDGs”

Introduction

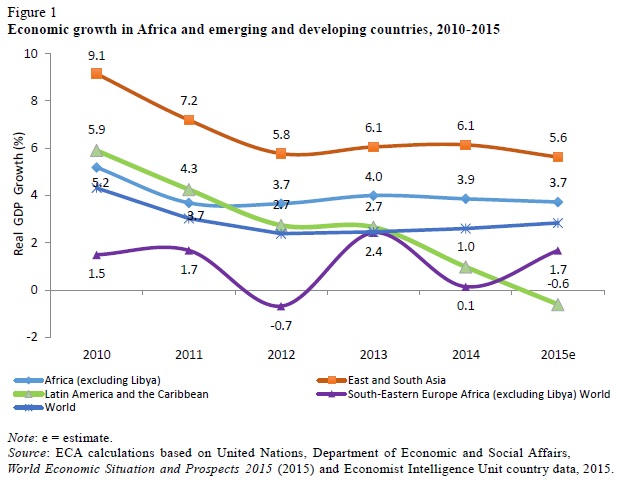

Africa’s economic growth declined moderately following the slight contraction in growth in the global economy, which was mainly due to subdued growth in emerging market and developing economies, while a modest recovery continued in developed economies. Looking forward, Africa’s real GDP growth is expected to increase by about 4.3 per cent in 2016 and 4.4 per cent in 2017.

Growth continues to be driven by strong domestic demand and investment (particularly in infrastructure). The improving business environment, lower costs of doing business and better macroeconomic management continue to enhance investment. The buoyant services sector and a focus on non-oil sectors by oil-exporting economies to mitigate the continued decline in oil prices will contribute to the positive medium-term prospects. In addition, the increasing trade and investment ties within Africa and between Africa and emerging economies as well as the recovery of traditional export markets, particularly in the eurozone, will positively contribute to the mediumterm prospects.

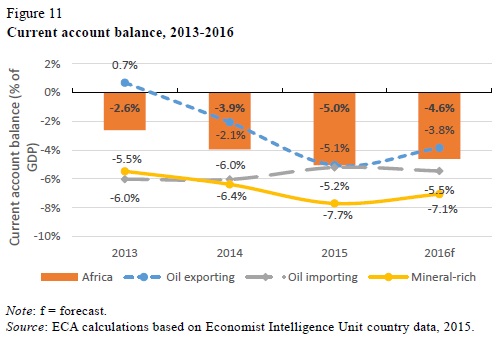

All the African subregions and economic groupings experienced current account deficits in 2015 that were driven to some extent by declining commodity prices, as oil-exporting countries recorded the first current account deficit since 2009 in 2014. On the other hand, low oil prices led to the narrowing of the deficit in oil-importing countries. Most African countries exercised tight monetary policy as global headwinds weighed on the region, mainly to curb rising inflation together with high fiscal and current account deficits. Inflation rates increased mainly as a consequence of weaker domestic currencies owing to declining commodity prices and rising food prices on the continent.

Africa’s medium-term prospects remain positive, despite the downside risks such as the current dry spell over the East and Southern parts of the region, which might significantly affect agricultural production as most of the economies are based on agriculture. The weak global economy, monetary tightening in developed economies and security and political instability concerns in some countries still remain a challenge.

Developments in the global economy and implications for Africa

Global growth declined moderately from 2.6 per cent in 2014 to 2.4 per cent in 2015, reflecting subdued growth in investment and household final consumption. The economic slowdown and rebalancing of economic activity in China away from investment and manufacturing towards consumption and services, lower prices for energy and other commodities (affecting economic activity in countries such as Brazil and the Russian Federation, as well as in other commodity-exporting countries) and gradual tightening in monetary policy in the United States are some of the key factors that have weighed negatively on global growth.

Growth in world trade remained subdued in 2015 at 2.6 per cent, the lowest rate since the global financial crisis, mainly owing to weak aggregate demand in emerging and developed economies, especially China and those in the euro area, the appreciation of the United States dollar against other currencies and rising geopolitical tensions in Iraq and the Syrian Arab Republic, and between Ukraine and the Russian Federation. These developments have had significant effects on trade in developing countries, including those in Africa. However, in the short term, trade growth is projected to accelerate to 4.0 per cent in 2016, thanks to strengthening demand from developed countries, which is expected to lift exports from developing countries.

The global outlook in the short term is slightly positive with growth projected at 2.9 per cent in 2016 reflecting a further increase in emerging and developing economies, in particular in Brazil, China and the Russian Federation, as well as in Middle Eastern countries and other Latin American countries. Nevertheless, the macroeconomic uncertainties that have persisted since the global financial crisis and the volatility of commodity prices will continue shaping the medium-term outlook. Against this backdrop of falling commodity prices, global growth patterns, declining trade flows, capital flows and diverging monetary policies, exchange rate volatilities have become more pronounced. The continued decline in oil prices, however, may generate a positive outlook for the African continent because of the number of oil importers, while oil exporters may see a deterioration of their current account balances and depreciation of their exchange rates.

The overall impact on Africa will strongly depend on the recovery in China and the euro area, which are Africa’s main trade partners. The political tension in Syria and some other parts of the Middle East, coupled with the issue of illegal migration facing the euro area, will also create serious concerns, as it will directly affect the demand side in Africa’s trade partners. Tightening monetary policy in the United States resulting in a muted increase in United States interest rates will also enhance the movement of capital outflows from developing and emerging economies.

Africa’s economic performance and prospects in 2015

Africa’s growth rate declined slightly from 3.9 per cent in 2014 to 3.7 per cent in 2015 owing to the global economic slowdown (see figure 1). Yet Africa’s growth is the second fastest after East and South Asia. Growth in Africa continues to be driven by domestic demand. Growth in private consumption is influenced by increased consumer confidence and an expanding middle class on the continent, while investment is driven mainly by an improved business environment and lower costs of doing business. Continued government spending on infrastructure projects, in particular, has also been positively contributing to growth. The external balance, however, had a negative impact on growth in 2015, as a result of weak and volatile commodity prices.

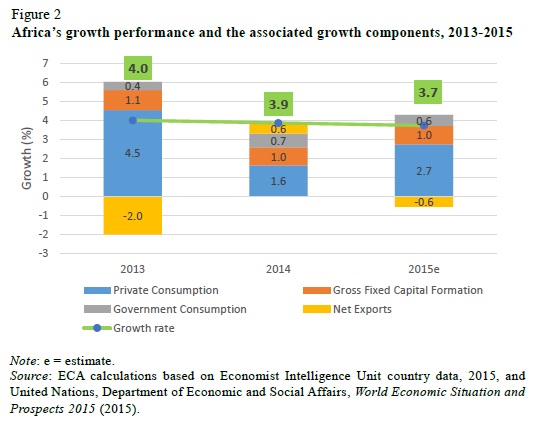

Private consumption continues to be the main driver of Africa’s growth

The contribution from private consumption grew from 1.6 per cent in 2014 to 2.7 per cent in 2015 (see figure 2). Despite the increase in infrastructure development on the continent, gross fixed capital formation contributed 1.0 percentage points to growth in 2015 (as was the case in 2014). This was mainly due to the reduction in capital inflows as a result of the slowdown in the global economy, especially among Africa’s development partners in the euro area and some emerging economies such as Brazil, China and the Russian Federation. Net exports continued to weigh negatively on growth in 2015.

Varying growth performance across economic groups and subregions

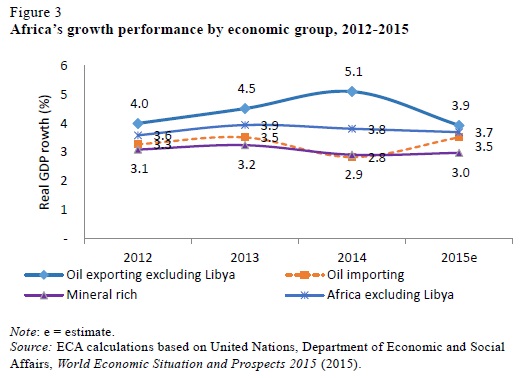

Despite the low oil prices, oil-exporting countries, with a 3.5 per cent growth rate, continue to perform well (as declining oil prices are partially cushioned by healthy dynamics in the non-oil sectors in some countries) as compared to both oil-importing and mineral-rich countries, with an average growth of 3.5 per cent and 3.0 per cent respectively (see figure 3). Growth in these two groups of countries is mainly driven by private consumption contributing 3.1 per cent and 3.2 per cent to growth, respectively.

Private consumption continued to be the main growth driver across subregions in 2015, despite the decline in its contribution to growth in East and Central Africa, mainly due to the global economic slowdown that has led to a reduction in investment flows to these subregions. However, it increased significantly in North, Southern and West Africa, contributing 2.2 per cent, 2.1 per cent and 3.4 per cent, respectively, to growth in 2015. Meanwhile, gross capital formation contributed significantly to growth in the East and North Africa subregions at 1.8 per cent and 1.6 per cent, respectively, mainly as a result of increased investments in infrastructure projects in both subregions.

At the subregional level, East Africa maintained the highest growth rate in the region at 6.2 per cent in 2015, despite experiencing a growth decline relative to 2014 levels, mainly as a consequence of lower growth in Ethiopia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Growth in West Africa decreased to 4.4 per cent in 2015, mainly driven by a more pronounced lower growth rate in Nigeria on the back of a weaker oil sector and power outages. The consequences of the 2014 Ebola outbreak in the most affected countries, namely Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone, also continued to weigh on these countries’ growth potential, despite Guinea and Liberia returning to positive growth.

The overall growth rate decreased slightly from 3.5 per cent in 2014 to 3.4 per cent in 2015 in the Central Africa subregion, despite its improved performance in the mining sector. While most countries in the subregion maintained a relatively high growth path, the security concerns in the Central African Republic and the decrease in oil production in Equatorial Guinea led to a decline in the subregion’s GDP.

Growth in North Africa (excluding Libya) accelerated from 2.8 per cent to 3.6 per cent over the 2014-2015 period. The positive developments have been helped by the improved political and economic stability in the subregion, and the subsequent increase in business confidence, especially in Egypt and Tunisia. A significant inflow of external aid into Egypt has enhanced public expenditure and boosted investment in large infrastructure projects, such as the expansion of the Suez Canal. The gradual recovery of export markets and improved security should support growth, especially through tourism. Political challenges in Libya continue to have a negative impact on both political and economic governance, as well as economic performance in the subregion.

Southern Africa’s growth increased marginally from 2.4 per cent in 2014 to 2.5 per cent in 2015. The improvement in growth performance of the subregion was heavily influenced by the relatively lower growth in its biggest economy, South Africa. Weak export demand and low prices for its key commodity exports, as well as electricity shortages, contributed to the country’s subdued performance. In Angola, GDP growth remained strong despite low oil prices, as the Government embarks on investing in strategic non-oil sectors such as electricity, construction and technology. Mozambique and Zambia recorded the highest growth in the subregion, driven by large infrastructure projects and FDI in the mining sector, respectively.

African countries’ growth still relies on a narrow base

While economic growth rates have been higher in Africa compared to most of the regions in the last decade, it is also clear that in many African countries growth has continued to rely on a narrow base. As a result, the number of Africans in absolute poverty has risen and inequality remains a major concern. More importantly, Africa’s economic growth has been associated with increased exploitation of non-renewable natural resources with minimal value addition and employment generation, and growth sustainability remains a major concern.

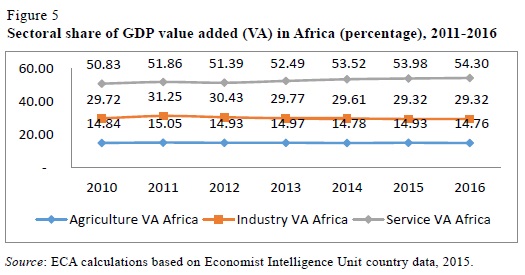

African economies are mainly dominated by the services sector followed by the industrial sector, with a marginal contribution from the agricultural sector (see figure 5). However, it has been widely recognized that industrialization is critical for Africa’s structural transformation and efforts to create jobs, foster value addition and increase income.

The impact of low oil prices on the growth of African economies is mixed

Crude oil prices continued to decline at a monthly average of 4.1 per cent over the period from June 2014 to October 2015. Robust supplies and lower demand due to the global economic slowdown have generally explained the decline in commodity prices across the board.

The Economic Commission for Africa (ECA) analysis using monthly data from January 2000 to October 2015 reveals that oil prices have had a significant positive impact in oil-importing and mineral-rich countries, but a negative impact on oil-exporting countries. Thus, the overall effect of low oil prices on Africa’s growth appears to be marginal. This marginal impact of the oil price decline emphasizes the significance of the continued diversification initiatives being undertaken by African countries, especially into non-oil sectors, and also the effect of improved macroeconomic management and the associated fiscal policies.

Low commodity prices and large investment projects underpin the growing fiscal deficits

Africa’s fiscal deficit increased from 5.1 per cent of GDP in 2014 to 5.6 per cent of GDP in 2015. The continued decline of oil prices and volatile commodity prices reduced fiscal revenues in many African countries, whereas high spending on infrastructure, fiscal loosening and higher spending in the lead-up to elections in a number of countries contributed to increased expenditure over the period. The fiscal deficit is expected to narrow in 2016 to 4.6 per cent of GDP as commodity prices and growth in emerging and developed economies are expected to pick up.

The fiscal deficit was the largest in North Africa, widening from 9.7 per cent of GDP in 2014 to 10.0 per cent of GDP in 2015. Over the period 2014- 2015, the fiscal deficit increased in West Africa (from 2.0 per cent to 2.5 per cent), in East Africa (from 3.8 to 4.6 per cent) and in Southern Africa (from 4.0 per cent to 4.3 per cent). The deterioration of the fiscal balance was greatest in Central Africa, where the deficit widened from 3.1 per cent in 2014 to 4.6 per cent of GDP in 2015.

The fiscal deficits of oil-rich countries reached their highest levels since 2012 at 5.7 per cent, largely driven by the low oil price. However, fiscal balances are projected to improve to 4.3 per cent of GDP in 2016 as commodity prices are envisaged to recover and as some oil exporters remove subsidies to alleviate pressure on their national budgets. However, with oil prices projected to remain below their recent peaks, fiscal revenues are not expected to return to earlier levels in oil-exporting countries.

Tight monetary policy amid falling commodity prices and declining revenues

African countries exercised tight monetary policy as global headwinds weighed on the region. As has been the case with most developing countries, the inflation rate rose from 7.0 per cent in 2014 to 7.5 per cent in 2015. The strong United States dollar and high food prices exerted inflationary pressures in the region, despite weak global growth and low commodity prices partially offsetting the rise in inflation. Currency devaluations, especially in the oil-rich countries, amid falling oil prices and declining revenues and exports also exacerbated the rise in inflation. These inflationary pressures, together with high fiscal and current account deficits, have led to the tightening of monetary conditions, including the hiking of monetary policy rates in countries such as Angola, Ghana, Kenya, Malawi, South Africa, Uganda and others to curb inflation. However, a moderating trend is expected for 2016 and 2017 in view of lower food and energy prices, improved security situations and diminishing impacts from subsidy cuts in 2014.

Exchange rates continued to depreciate, although with minimal impact on exports

Most African currencies depreciated in 2015, a trend that started in 2014. This was driven partly by low oil prices, but also the strong dollar and the expected tightening of the United States monetary policy.

Currency depreciation is expected to be associated with increased exports and a decrease in imports. However, for African countries the association between exchange rate and trade seems to be very weak and, in some countries, not in line with the theory. This could suggest that there are other factors behind Africa’s lack of competitiveness, which undermine the benefits brought about by currency depreciation. While the cost of doing business in Africa has been decreasing, there are still considerable barriers to enhancing Africa’s trade, suggesting a lack of product diversification and value addition.

Current account deficits recorded by all economic groupings and subregions

Current account deficits increased from -3.9 per cent in 2014 to -5.0 per cent of GDP in 2015, with all economic groupings and subregions reporting deficits (see figure 11). Declining commodity prices and global demand as a result of the global economic slowdown, especially in emerging economies, played a significant role in the current account trends, with oil-exporting African countries recording their first current account deficit since 2009 (2.1 per cent) in 2014, followed by a deficit of 5.1 per cent in 2015. For oil importers, the low oil prices led to a narrowing of the deficit. Of the subregions, the current account deficit was largest for Central Africa (8.1 per cent), followed by East Africa (7.4 per cent) and then Southern Africa (5.7 per cent).

Africa’s total exports of goods and services declined by 3.2 per cent in 2013 and 5.2 per cent in 2014, while its total imports grew by 3.0 per cent in 2013 and by 1.7 per cent in 2014. The continent’s total imports are dominated by consumer goods, whereas its exports consist mainly of primary commodities, including fuels and bituminous minerals, and agricultural products such as cocoa, fruits, fertilizers and vegetables. In terms of value, in 2014 fuel exports decreased by 13.2 per cent, and ore and metal exports by 8.2 per cent. On a positive note, whereas Africa’s exports to most of its trading partners have stagnated or even declined since the 2008 financial and economic crises, intra-African trade has since then increased considerably in terms of both volume and diversification of manufactured products and services.

Stable FDI with declining reserves and increasing net debt among African countries

African countries saw FDI remain stable at around 3 per cent of GDP in 2015, and are expected to remain at this level in 2016 and 2017. The recovery in North Africa was reflected in the pickup in FDI inflows from 1.4 per cent in 2014 to 1.7 per cent in 2015. Southern Africa (in particular, Angola, Mozambique, South Africa and Zambia) and Central Africa have been the main destinations for FDI. East Africa (particularly Ethiopia, Kenya and Tanzania) also attracted a significant amount of investment, especially in infrastructure.

In terms of business function, manufacturing represents 33.0 per cent of FDI, while extraction remains at 26.0 per cent and construction at 14.0 per cent of FDI. By sector however, coal, oil and natural gas dominate at 38.0 per cent of FDI. Therefore, there is still scope for diversification from primary commodities and construction-related investments. FDI into Africa has partly been driven by strong economic growth in key economies, but also the low interest rates in the United States and Europe in 2015, which led to an increase in the flow of FDI into emerging economies. However, with the expectations of monetary tightening by the United States (which finally took place in December 2015), FDI inflows may have started being diverted back to mature markets.

The falling oil and commodity prices drew down the international reserves of African countries from 17.1 per cent of GDP in 2014 to 15.8 per cent of GDP in 2015. The oil price decline also affected the net debt of African economies, which increased from 5.8 per cent to 9.9 per cent of GDP between 2014 and 2015, compared to 1.6 per cent in 2013, and is projected to rise further to 11.4 per cent in 2016.

Medium-term growth prospects and risks

Looking forward, Africa’s real GDP growth is expected to increase by about 4.3 per cent in 2016 and 4.4 per cent in 2017. Growth continues to be driven by strong domestic demand (particularly investment in infrastructure). The improving business environment, lower costs of doing business and better macroeconomic management continue to enhance investment. The buoyant services sector and a focus on non-oil sectors by oilexporting economies in order to mitigate the continued decline in oil prices will contribute to the good medium-term prospects. Further, the increasing trade and investment ties within Africa and with emerging economies, as well as the recovery of traditional export markets, particularly in the eurozone, will positively contribute to the medium-term prospects.

At the subregional level, Southern Africa and West Africa are expected to experience relatively high real GDP growth both in 2016 and 2017; while real GDP growth in Central, East and North Africa is forecasted to increase in 2016, but with a slight decline in 2017. However, African economies face significant risks that require special attention by policymakers to maintain the requisite growth. More importantly, the turbulence in the global economy has been underpinned by severe financial instability, widening sovereign-debt problems and high unemployment, especially in developed economies. Africa’s vulnerability to these shocks calls for a rethink of its growth and broader development strategy.

Weather-related shocks, such as drought in East and some parts of Southern Africa in particular, pose a challenge to the agricultural sector, which is still the main employer in most African countries. Low harvests will also increase the risk of inflation through higher food prices in the affected countries. These dry spells may also affect the hydropower generation capacity in the affected countries, hence posing a threat to the greening of Africa’s industrialization, as economic agents may switch to thermal electricity power generation that is not green.

Security concerns and political unrest in some countries also remain an issue as they can lead to domestic disruption and decreased investment in these countries.

Recent social developments in Africa

Africa made considerable progress towards achieving the Millennium Development Goals despite challenging initial conditions. The baseline, generally 1990 for most of the Millennium Development Goals, was relatively low compared to other developing regions. There is an overall positive direction, with significant proportions of progress with variation across certain Goals, across and within countries.

Status of progress towards social outcomes in Africa

In Africa (excluding North Africa), poverty levels have dropped, although at a slow pace, from 56.5 per cent to 48.4 per cent between 1990 and 2010. The proportion of Africa’s population facing hunger and malnutrition demonstrated a meagre 8 per cent improvement between 1990 and 2013.

Africa is close to achieving universal primary enrolment in 2013, with over 68 per cent of the 25 countries (with data available) achieving a net enrolment rate of at least 75 per cent. However, the completion rates reported are still at 67 per cent, denoting that education quality is lagging behind quantitative gains. Gender parity in primary schooling improved from 0.86 before 2012 to 0.93 after 2012, but secondary and tertiary gender parity are at 0.91 and 0.87 respectively, which is still below the 0.93 benchmark.

Under-5 mortality fell from 146 deaths per 1,000 live births in 1990 to 65 deaths per 1,000 live births in 2012, an improvement of 55.5 percentage points compared to the Millennium Development Goal 4 target of a two-thirds (67 per cent) reduction by 2015. The efforts to combat HIV/AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis have yielded some noteworthy achievements in terms of incidence, prevalence and mortality rates.

Progress towards the environmental goal has been somewhat lacklustre. Only a quarter of Africa’s population have gained access to improved drinking water sources, which is the lowest proportion globally. Similarly, the proportion of people with access to improved sanitation has increased from 24 per cent in 1990 to 30 per cent in 2012. However, the disaggregated figure of both improved access to water and sanitation is skewed towards urban areas. The inadequate attention paid to rural areas and communities in terms of rural infrastructure combined with population growth results in land degradation, decreasing agricultural productivity, lower incomes and reduced food security.

Despite the good progress registered, there are inequities based on income, gender, ethnicity and location. In terms of the human development index (HDI), which measures average achievements in three basic dimensions of human development, a long and healthy life, knowledge and a decent standard of living, most African countries are in the lower ranks of human development. The inequality-adjusted HDI value drops by 33 per cent, the highest drop globally.

Employment mostly generated outside the formal economy

Unemployment rates for Africa (excluding North Africa), disaggregated by sex, were 6.9 per cent for males and 8.8 per cent for females in 2014, which represent marginal declines of 0.2 and 0.1 percentage points over the 2009 rates. Notably, economic growth has not kept pace with employment growth, largely because growth has been driven predominantly by capital-intensive sectors such as mining and oil, and the export of primary commodities with little value addition, among others.

Most jobs in Africa, particularly for the youth and women, continue to be generated outside the formal economy, where the skills profile is predominantly poor. It is further observed that 9 in 10 rural and urban workers in Africa have informal jobs, and most employees are women and the youth.

Over the next 10 years, at best only one in four youths will find a wage job, and only a small fraction of those jobs will be “formal” in modern enterprises. Thus, the informal economy is the major source of employment on the continent, accounting for nearly 70 per cent in East, Central, Southern and West Africa, and 62 per cent in North Africa.

However, the working-age population is growing more rapidly

The active working-age population (25-64 years) is growing more rapidly than any other age group, more than tripling in size between 1980 and 2015, when it stood at 123.7 million (33.3 per cent) and 425.7 million (36.5 per cent), respectively. The active working group is largely composed of young people, and its growth over time is a feature of the demographic dividend that could lead to productivity gains and economic growth in Africa. The demographic dividend depends on the young population having the right skills profile to secure the positive effects.

Africa will have the highest urban growth rate

Over the period 2015-2020, Africa will experience the highest rate of urban growth globally, with a rate of 3.42 per cent annually compared to the world rate of 1.84 per cent over the same period. The percentage of Africa’s population that is urban increased from 27 per cent in 1980 to 40 per cent in 2015, and is expected to pass the 50 per cent mark by 2035. This will be accompanied by a considerable rise in demand for urban services, infrastructure and employment, all of which are already severely constrained.

Beyond the demographic shift, urban areas currently contribute more than 55 per cent of GDP to African economies. The economic role of cities, however, is largely driven by consumption rather than production. Unlike other parts of the world, urbanization in Africa is not linked to industrialization, which in turn has led to “consumption cities” that are populated primarily by workers in non-tradable services. Moreover, African cities remain largely informal. This is particularly problematic given the youth bulge in the region, and the concomitant need to create decent jobs.

Urban growth in Africa is also expected to be accompanied by increased energy and resource demands, with the associated impacts on ecosystems supporting urban areas. Globally, urban areas account for over 70 per cent of greenhouse gas emissions. African cities have comparatively lower carbon dioxide emissions, but this is projected to increase significantly in the absence of strategies for urban resource and energy efficiency. Evidence points to the importance of decoupling at the city level to reduce environmental impacts and enhance resource efficiency and productivity, especially by promoting compact cities. As the least urbanized region globally, Africa has a unique opportunity to minimize the carbon footprint of its cities through infrastructure and land use practices that promote density and reduced car-dependence and fossil fuel energy consumption.

Given the growing demographic, economic and environmental significance of urban growth in Africa, cities need to be accounted for in the continent’s green economy agenda. In particular, urban agglomeration leads to resource efficiency and economies of scale in industrial production through intra-industry and inter-industry interactions. If it is to be resource- and energyefficient, Africa’s industrialization requires an efficient framework of urban centres that produce industrial goods and high value services, along with transportation networks to link national economies with regional and global markets. Greening Africa’s industrialization thus needs to be linked to the urban transition underway in the region.

Policy implications

African countries have made notable gains in improving their regional business environment. Together with the increased economic and political stability across most subregions, these gains have supported growth through enhancement of private consumption and increased public and private investment. However, the recent commodity price developments have highlighted the persistent structural weaknesses of many economies, particularly in terms of government revenue, exchange rates and current account balances. This calls for a stronger emphasis on strategic non-oil sectors, such as electricity, construction and technology, particularly in economies heavily dependent on oil revenue.

The global economic environment has increased the need for prudent and counter-cyclical macroeconomic management strategies. The continued low prices offer an opportunity for improved fiscal management and consolidation through the cutting of utility subsidies. Expenditure should instead be targeting high-priority sectors with emphasis on strategic non-oil sectors for accelerated structural transformation.

With Africa’s continued exportation of commodities, the current global economic slowdown underscores the need for Africa to figure out how it could extract more value from its global trade and other economic activities. Given the more diversified nature of trade between African countries relative to trade with the rest of the world, intra-African trade provides an opportunity for diversification of production. At the same time, diversification of trade patterns can also be a source of improved resilience to external shocks. African countries should seek to enhance intra-African trade by strengthening regional integration, lowering the cost of trade and non-physical barriers to trade, and making a strong commitment to the continental free trade area that is under negotiation.

Economic growth rates have been higher in Africa compared to most regions in the last decade; however, in many African countries growth has not been inclusive, the number of Africans in absolute poverty has risen and inequality remains a major concern. This is mostly because Africa’s economic growth has been associated with increased exploitation of non-renewable natural resources with minimal value addition and employment generation, which undermines its growth sustainability.

The growth of an unplanned urban Africa with a youthful population needs to be matched with an industrialization process that provides the skills demanded and efficient and adequate public services delivery. The focus on the current, largely young and female, informal sector workers to drive the new agenda is a vital aspect of an industrialization process. It is feasible to increase productivity and contribute to improved welfare in the informal sector by providing training, access to credit and social protection.

As most African economies are based on agriculture, a sector dependent on rainfall, they are vulnerable to climate variability. Given that sustainability has been placed at centre stage in the process of industrialization, environmental standards should be seen not as an obstacle to competitiveness, but as a potential driver of growth. Africa must improve its resilience to both environmental and socioeconomic shocks, manage its natural capital and minimize pollution, all of which can be achieved by greening its industrialization process.

The continent’s industrialization and broader development has been held back by erratic energy supplies. The importance of reliable and sustainable energy sources for structural transformation cannot be overemphasized. Africa must tap into and use renewable energy resources to avoid the mistake that developed countries made by not taking into consideration renewable energy issues.