News

World Bank report finds rise in global wealth, but inequality persists

Report goes beyond GDP to assess the economic progress of nations

Global wealth grew significantly over the past two decades but per capita wealth declined or stagnated in more than two dozen countries in various income brackets, says a new World Bank report. Going beyond traditional measures such as GDP, the report uses wealth to monitor countries’ economic progress and sustainability.

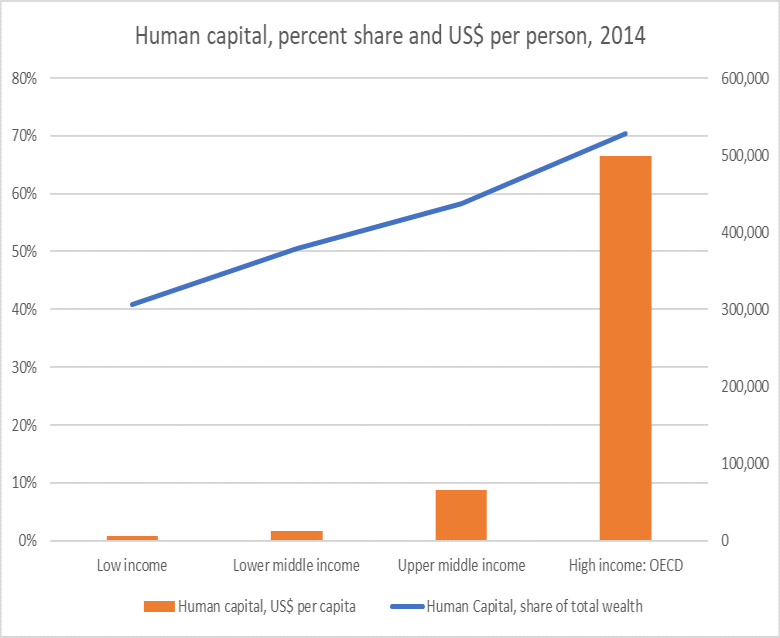

The Changing Wealth of Nations 2018 tracks the wealth of 141 countries between 1995 and 2014 by aggregating natural capital (such as forests and minerals), human capital (earnings over a person’s lifetime); produced capital (buildings, infrastructure, etc.) and net foreign assets. Human capital was the largest component of wealth overall while natural capital made up nearly half of wealth in low-income countries, the report found.

“By building and fostering human and natural capital, countries around the world can bolster wealth and grow stronger. The World Bank Group is accelerating its effort to help countries invest more – and more effectively – in their people,” said World Bank Group President Jim Yong Kim. “There cannot be sustained and reliable development if we don’t consider human capital as the largest component of the wealth of nations.”

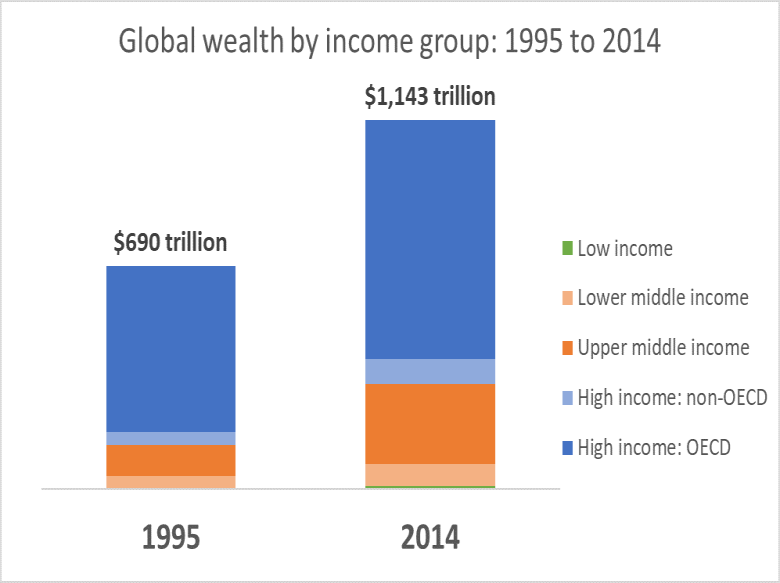

The report found that global wealth grew an estimated 66 percent (from $690 trillion to $1,143 trillion in constant 2014 U.S. dollars at market prices). But inequality was substantial, as wealth per capita in high-income OECD countries was 52 times greater than in low-income countries.

A decline in per capita wealth was recorded in several large low-income countries, some carbon-rich countries in the Middle East, and a few high-income OECD countries affected by the 2009 financial crisis. Declining per capita wealth implies that assets critical for generating future income may be depleted, a fact not often reflected in national GDP growth figures.

The report found that more than two dozen low-income countries, where natural capital dominated overall wealth in 1995, moved to middle-income status over the last two decades, in part by investing earnings from natural capital into sectors such as infrastructure, as well as education and health which increase human capital.

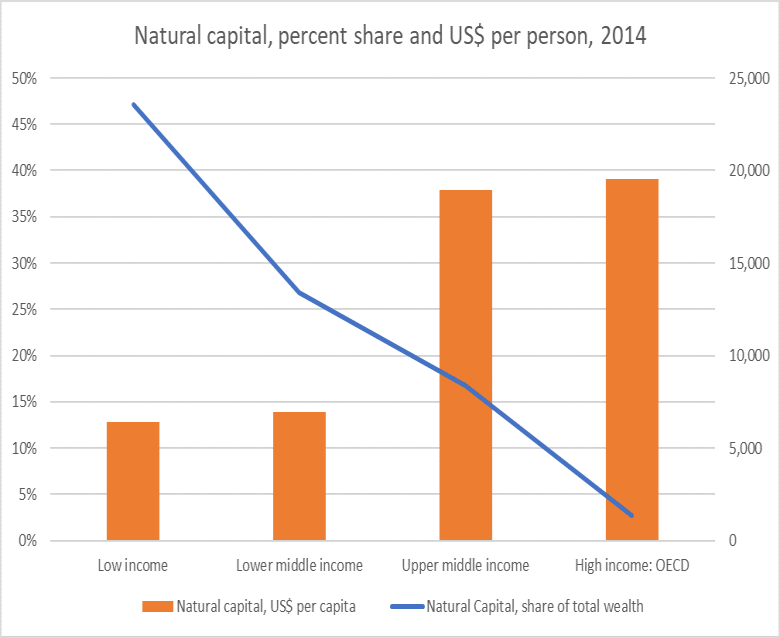

While investments in human as well as produced capital are essential, getting rich is not about liquidating natural capital to build other assets, the report notes. Natural capital per person in OECD countries is three times higher than in low-income countries, even though the share of natural capital in total wealth is just 3 percent in OECD countries.

“Growth will be short-term if it is based on depleting natural capital such as forests and fisheries. What our research has shown is that the value of natural capital per person tends to rise with income. This contradicts traditional wisdom that development necessarily entails depletion of natural resources,” said Karin Kemper, Senior Director, Environment and Natural Resources Global Practice at The World Bank.

The report estimated that the value of natural capital assets doubled globally between 1995 and 2014. This is due, among other reasons, to increased commodity prices along with a rise in economically-proven reserves. In contrast, productive forest value declined by 9 percent while agricultural land expanded at the cost of forests in many areas.

The latest report, which follows similar World Bank assessments in 2006 and 2011, includes estimates of human capital for the first time. Human capital is measured as the value of earnings over a person’s remaining work life, thereby incorporating the roles of health and education. Women account for less than 40 percent of global human capital because of lower lifetime earnings. Achieving gender equity could increase human capital wealth by 18 percent.

Human capital accounts globally for two thirds of global wealth; produced capital accounts for a quarter of wealth. Natural capital accounts for one tenth of global wealth, but it remains the largest component of wealth in low-income countries (47 percent in 2014) and accounts for more than one-quarter of wealth in lower-middle income countries.

Wealth accounts for countries are compiled from publicly available data drawn from globally recognized data sources and with a methodology that is consistent across all countries. Some wealth components from natural capital were not tracked in the report, including water, fisheries and renewable energy sources.

The report was funded in part by the WAVES (Wealth Accounting and the Valuation of Ecosystem Services) partnership and by the Global Partnership for Education.

Top three findings from the report

Despite rising global wealth, inequality persists

The world is still unequal when seen through the lens of wealth. High-income OECD countries hold 52 times more wealth per capita, measured at market exchange rates, than low-income countries.

More than two dozen countries saw their per capita wealth decline or stagnate. Declining per capita wealth implies that assets critical for generating future income may be depleted, a fact not often reflected in national GDP growth figures. This included several large low-income countries, some carbon-rich countries in the Middle East, and a few high-income OECD countries affected by the 2009 financial crisis.

In low-income countries, wealth almost doubled, a larger increase than the global average of a 66% rise. But higher population growth in many low-income countries means that, in those countries, per capita wealth often grew at a slower pace than the global average. This is particularly true for Sub-Saharan Africa, where the needle on wealth per capita did not move much since 1995.

Importance of investing in people

Human capital accounts for two thirds of global wealth, the largest chunk of wealth. The report shows that human capital is about 70% of the wealth in high-income countries and only 40% in low-income countries. Human capital is computed as the present value of future earnings for the labor force, factoring in education and skills as well as experience and the likelihood of labor force participation at various ages. This report makes a clear economic case for investing in human capital to boost wealth and future economic growth.

Leveraging Natural capital but not liquidating it

Natural capital remains the largest share of wealth for low-income countries. In 10 of the 24 low-income countries, natural capital accounts for more than 50% of their wealth, mostly because of agricultural land and forests. The fact that the share of natural capital in total wealth decreases in higher-income groups means that countries do not have to liquidate natural assets to grow. Instead, it points to the need to manage natural capital so that it increases in value for future generations. This is reflected in the wealth composition of high-income countries, where the value of natural capital is three times that of low-income countries.

Low-income countries have the opportunity to grow by building their renewable resources like forests and sustainable management of land, which often make up a larger share of their assets. Rents from non-renewables like minerals and fossil fuels can be used to build other assets like infrastructure and human capital, that can continue to generate income even after minerals are exhausted.

Way forward

While this book pushes the boundaries on wealth accounts, there is widespread recognition that the scope and the scale of this research can be further expanded. The next frontier on natural capital includes looking at resources currently missing due to lack of data: water, fish stocks, renewable energy sources, and several critical ecosystem services. The World Bank is also working on two follow-up studies building on the estimates of human capital. The first will look at the cost of gender inequality globally, and the second will use the human capital data to look at the benefits, among others, of reducing stunting, investing in education, or ending child marriage.

The hope is that thinking about wealth will become more mainstream and help countries to better balance their portfolio of assets for long-term sustainable growth and prosperity.