News

South Africa: Latest IMF outlook shows urgent need for policy reforms

South Africa faces significant challenges and needs decisive action to revive growth, the IMF said in its latest annual assessment of the country’s economy.

South Africa has made considerable economic and social progress since its first democratic election in 1994, but many citizens have not sufficiently benefited from the improvements. The report shows income inequality and unemployment remain among the highest in the world, and growth has waned in recent years.

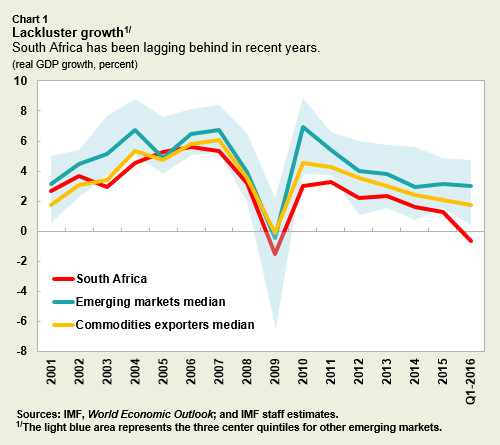

In 2015, South Africa was hit by a number of economic shocks. China’s slowdown and rebalancing, weak commodity prices, and U.S. monetary policy normalization all weighed on growth (Chart 1). On the domestic front, leadership changes at the National Treasury last December and other political developments shook confidence, heightened governance concerns, and increased policy uncertainty. A severe drought in the region also significantly reduced agricultural output.

And while electricity supply has improved, growth continues to be held back by deep-rooted structural problems such as poor education outcomes, and product and labor markets that are out of reach for too many people.

The report shows growth slowed to 1.3 percent in 2015, the lowest since the global financial crisis and below most emerging market economies and commodity producers. The IMF projects 2016 growth at 0.1 percent, which would mean a second year of falling per capita incomes. A muted recovery is expected from 2017, approaching 2-2½ percent in the outer years as shocks dissipate and more power plants are completed; with these projections, unemployment will likely rise over the medium term.

Risks of further deterioration

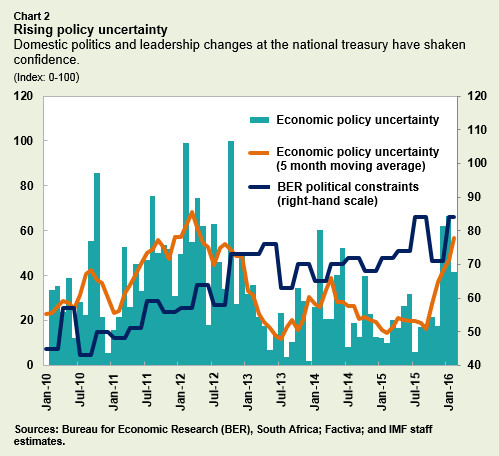

Downside risks dominate and stem mainly from China, heightened global financial volatility, and domestic politics and policies that may reduce confidence (Chart 2).

Shocks could be amplified by linkages between capital flows, the sovereign, and the financial sector, especially if combined with sovereign credit rating downgrades to speculative grade. The United Kingdom’s recent decision to leave the European Union (EU) has further increased risks, as there are extensive financial linkages between the United Kingdom and South Africa and sizable trade linkages with the EU as a whole.

The report notes, however, that the authorities are making progress in the recent dialogue between government, businesses, and labor, which could catalyze reform implementation and invigorate growth.

Urgent need for more reforms

Besides addressing infrastructure bottlenecks, the report said structural reforms should be a priority in order to boost growth and jobs. Greater competition, labor market policies and industrial relations that work for a greater portion of the population, better quality of government services – especially in education – and improved governance and efficiency in state-owned enterprises would all help increase growth.

Job creation, especially in small- and medium-sized enterprises that are more labor-intensive and hire a relatively high share of low-skilled workers, is the best way to ensure a sustainable reduction in unemployment and inequality. Advancing these reforms will require building trust among stakeholders, ideally via a social bargain.

To generate reform momentum, the report suggests government should implement a focused set of tangible measures with a priority on boosting private sector employment. Clarifying the regulatory environment in the mining sector and reforming state-owned enterprises, for example, would reduce policy uncertainty and increase confidence and trust even in the short term.

Elevated vulnerabilities

Sources of resilience include strong institutions and policy frameworks, the flexible exchange rate regime, strong private corporate balance sheets, a high share of rand-denominated external debt, well-capitalized banks, and the large domestic institutional investor base.

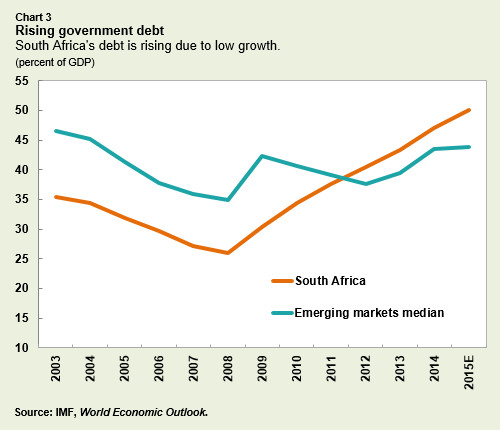

Nevertheless, vulnerabilities remain elevated. The current account deficit, though it has started adjusting, remains among the highest in emerging markets. Rising government debt, due to a large extent to low growth, and financially-weak state-owned enterprises have increased fiscal vulnerabilities, and sovereign downgrades could trigger capital outflows (Chart 3).

Limited macroeconomic policy space

The 2016 budget envisaged significant deficit reduction this year and next to stabilize debt. However, the budget targets could be challenging to achieve if IMF staff’s less-optimistic growth projections materialize. The report suggests that any additional fiscal consolidation needs to be carefully designed to minimize the negative growth impact and protect the poor. State-owned enterprise reforms are also essential to limit fiscal risks, as well as to support growth. Greater private participation and effective regulators could help improve state-owned enterprise performance and free up resources for investment.

Making a strong push on structural reforms is the absolute, urgent priority to put the South African economy on a path to improving living standards and create jobs, the report said.

Context: Confluence of shocks on top of existing structural challenges and vulnerabilities

The global transitions – China’s slowdown and rebalancing, weak commodity prices, and the U.S. monetary policy normalization – are taking a heavy toll on South Africa. China’s key role in the world economy and South Africa’s high reliance on mining exports result in significant spillovers from China’s transitions and the commodity price fall, despite the country being an oil importer (Box 1). China’s growth now matters more for South Africa than the E.U.’s and the U.S.’s growth.

Commodities are the main channel, closely followed by global financing conditions likely capturing confidence effects. The commodity channel is also likely operating via Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) – now absorbing 30 percent of South Africa’s exports and a major destination of South African corporates’ large expansion abroad – and is reducing corporate profitability and incomes across the economy. In addition, South Africa’s financing conditions are closely tied to those in the United States, though the two economies are moving in opposite directions. Outward spillovers to South Africa’s immediate neighbors will be significant. Spillovers to the rest of SSA are rising but remain muted (Box 2).

Box 1. Spillovers from Global Transitions

Spillovers from China and lower commodity prices

Rising trade linkages and reliance on commodities have increased spillovers from China. China absorbs 10 percent of South African exports, the most of any country. More importantly, it plays a key role in determining global demand for South Africa’s commodity exports, which account for 34 percent of total goods exports (51 percent including manufactured commodities), and commodities imports including oil, which account for 16 percent of total goods imports.

Staff analysis suggests China’s growth now matters more for South Africa than that of the U.S. and the E.U. Using quarterly data from 2000, a VAR suggests that a one percentage point decline in China’s real GDP growth would lower South Africa’s growth by 0.3 percentage point (q/q sa annualized) after one quarter. This is smaller than the impact of a shock to the U.S. and the E.U. growth, and broadly consistent with estimates found in previous studies, including the World Bank’s June 2015 Global Economic Perspectives. However, the impact of a shock to China’s growth rises to 1 percentage point in the postcrisis sample, significantly exceeding the impact of shocks originating in the U.S. and the E.U. Though data limitations preclude a full analysis, the impact of a decline in China’s secondary sector could be even greater.

Commodity prices and global financial conditions are the main transmission channels. A decomposition following Swiston and Bayoumi (2008) suggests the decline in South Africa’s export commodity prices following a shock to China’s growth has a large and persistent impact. Financial spillovers (proxied by U.S. financial conditions), which likely capture global confidence effects, are also important. Spillovers through trade are small and positive, suggesting the impact of exchange rate depreciation on competitiveness outweighs the fall in global demand. Declining import commodity prices (mainly oil) provide a partial offset.

The impact of lower commodity prices is amplified by sectoral interlinkages. An analysis of input-output tables in South Africa suggests linkages between the commodity sector and the rest of the economy are significant. A sectoral structural VAR identified using multipliers from the input-output table suggests a 10 percentage point decline in export commodity prices would reduce real GDP growth by nearly 0.2 percentage points (q/q sa annualized) after two quarters, with most of the impact coming from downstream (e.g., construction) and upstream (e.g., transport) sectors including manufactured commodities. A Swiston and Bayoumi decomposition suggests that the main transmission channels are changes in corporate profitability and employment in the non-mining sector.

A shock to China’s growth worsens South Africa’s external and fiscal balances, but the impact on inflation is ambiguous. Mineral export growth declined to -7 percent in 2015 from an average of 19 percent in 2011-13 on lower demand and prices. The lower oil import bill is a partial offset, and the terms of trade are expected to remain negative over the next few years.3 Fiscal revenues are affected mainly through growth, with corporate income tax growth down from an average of 10 percent between FY11/12-FY13/14 to an estimated 2.2 percent in FY15/16. Lower oil prices are fully passed through to retail prices, with petrol prices in early-2015 27 percent below their 2014 peak. However, this effect has been partly offset by depreciation. Anecdotal evidence points to a significant deflationary impact from overcapacity in China, which South Africa has partly offset through increasing tariffs by 10 percent on some steel imports (within the WTO bound rates). The overall impact on inflation in South Africa is therefore ambiguous.

Spillovers from tighter global financial conditions

High external financing needs and a large share of bond and equities held by foreign investors make South Africa vulnerable to spillovers from tighter global financial conditions. Almost half of South Africa’s portfolio liabilities are held by U.S. investors. Estimates in Caceres et al. (2016) suggest a 100bps increase in the U.S. policy rate would increase South African long-term rates by 73bps after one year, above the EM average, but short-term rates are not significantly affected. 4 South Africa-specific estimates underlying the 2014 Spillover Report suggest a 0.2 percent decline in growth after one year following a 100bps rise in U.S. bond yields, with most of the spillovers coming from a 79bps increase in long-term bond yields and declining equity prices. Simulations using a broader set of countries in the 2015 Spillover Report and in Buitron and Vesperoni (2016) suggest that an unexpected tightening of monetary conditions that pushes up U.S. bond yields by 100 bps would spill over to bond yields in EMs and non-systemic advanced countries, result in capital outflows, and lower industrial production growth by 3½ percent per annum after one year. Most EMs would also experience significant exchange rate depreciation, though South Africa is relatively shielded from negative balance sheet effects given low corporate leverage and limited FX mismatches.

Box 2. Outward Spillovers to Sub-Saharan Africa

Past research suggests that, apart from its immediate neighbors, South Africa has limited spillovers to the rest of Africa, but these are likely to have increased. Several studies have shown that South Africa’s growth has limited spillovers on SSA, once global growth is controlled for. However, SSA’s share in South Africa’s imports has more than doubled over the last decade. South African companies in retail, banking, and telecommunications have established large networks in several sub-Saharan African countries. South Africa now represents an important export destination and source of FDI, especially for neighboring countries.

Other countries of the Southern African Customs Union (SACU) will be the most affected by South Africa’s slowdown. Besides the growth impact, SACU countries rely heavily on South Africa in their shared customs receipts, as South Africa accounts for about 85 percent of total SACU imports. With imports having declined in 2015 and low growth expected going forward, combined with the lags built in the SACU revenue formula, this vital source of revenue will decline markedly.

South African firms have many subsidiaries in SSA, which could dampen their profitability going forward. About 75 percent of African subsidiaries are in services, trade, and financial sectors. The 10 firms with the highest number of subsidiaries are some of the top listed companies. While African subsidiaries have contributed to South African corporates’ high profitability in the past decade, the deteriorating performance of SSA could adversely affect profitability.

Selected Issues Paper

The impact of China’s growth slowdown and lower commodity prices on South Africa

This paper estimates the impact of China’s growth slowdown and the recent large decline in commodity prices on South Africa. It seeks to identify the key channels through which a shock to China’s economy is transmitted to South Africa, as well as the propagation of this shock within the economy. Our findings suggest that China’s growth slowdown is likely to have a significant impact on South Africa’s economy, with commodity prices and global financial conditions the main transmission channels. Sectoral interlinkages are found to play an important amplifying effect, notably through employment, corporate profitability, and wealth effects.

Increasing trade linkages have made China the most important single-country destination for South African exports. China now absorbs 10 percent of South African exports compared to around 2½ percent in the mid-2000s. This trend reflects not only rapid growth in China and the associated rise in China’s demand for commodities, but also weak demand from the Euro Area whose share of South Africa’s exports has declined to 15 percent from more than 20 percent over the same period. Sub-Sarahan Africa (SSA) remains the most important regional destination for South African exports

China’s impact on the South African economy is magnified by China’s role in the global economy and commodity markets.

-

China accounts for around 17 percent of global output in PPP terms compared to 16 percent for the US. In terms of imports, China accounted for approximately 16 percent of the world total compared to 14 percent for the U.S.

-

More than 60 percent of the world’s traded iron ore – South Africa’s main mineral export – is absorbed by China. China also plays a large role in other commodities that South Africa exports including coal, gold, and platinum. As a result, China plays a key role in determining global demand and prices of South Africa’s main commodity exports, which now account for 34 percent of total goods exports (51 percent when manufactured commodities are included). China is also one of the world’s largest oil importers, and therefore plays an important role in setting the price of South Africa’s oil imports (though supply factors have been key for prices), which account for around 16 percent of total goods imports.

Capital flows into South Africa from China are modest, but financial spillovers are increasing. Both direct investment and portfolio flows from China are increasing, but remain modest relative to capital flows from the UK and the US. However, as noted in the April 2016 Global Financial Stability Report, financial conditions in China are now increasingly affecting global financial conditions, mainly through equity and FX markets.

China’s growth has been found to have large spillover effects on South Africa, transmitted mainly through commodity prices and global financial conditions, and amplified by sectoral interlinkages. The analysis in this paper suggests that rising trade and financial linkages with China, as well as China’s large role in the global economy and commodity markets, has increased the impact of a growth slowdown in China, which now exceeds that of a growth slowdown in the U.S. and the E.U. Commodity prices and tighter global financial conditions are the main international transmission channels. Domestically, the impact of a fall in commodity export prices is amplified by linkages between the mining and non-mining sectors, and is transmitted to the economy through large falls in mining sector employment, corporate profitability, and wealth effects.

Macro-financial linkages: capital flows, sovereign ratings, and the financial sector nexus

This paper discusses key macro-financial linkages and related risks in the South African economy focusing on downside scenarios that are not part of the baseline. South Africa’s high reliance on external finance, with banks intermediating a larger share of capital flows in recent years, exposes it to the risk of capital flow shocks. Low growth, rising interest rates, and fiscal risks could generate negative feedback loops among lower capital flows, heightened sovereign risk, and a weaker financial sector. The confluence of these factors could raise financial institutions’ funding and credit costs, and widen the fiscal deficit given the high reliance of tax revenues on the financial sector.

While so far the financial sector has not hampered growth, a weaker financial sector could reduce lending, and in turn lower growth. Sovereign rating downgrades are a possible trigger of capital outflows. A downgrade of the sovereign foreign currency (FX) debt to speculative grade seems to be mostly priced in and is likely to have a limited impact on the sovereign given the low level of government FX debt. A potential downgrade of the local currency (LC) sovereign debt rating to speculative grade is not in staff’s baseline, as the latter is currently two to three notches above non-investment grade. If it were to happen, however, it could trigger sizable capital outflows and generate some of the feedback loops described above, given large non-resident holdings of government debt, about a fifth of which are estimated to require investment grade rating. The floating exchange rate regime and South Africa’s deep capital markets are likely to mitigate such shocks.